100 Years of Insulin

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, the FDA History Office provides the following overview of major milestones in the regulation of this life-saving drug.

DIABETES AND ITS TREATMENT BEFORE 1920

The symptoms often associated with uncontrolled diabetes, including extreme thirst, hunger, and the need for urination, along with fatigue and systematic wasting, have been known for millennia. A recognition that those suffering this affliction also had sweetened urine came quite early as well. A more detailed understanding of the pathology of diabetes grew over the years, such as its effect on the micro- and macrovascular vessels that could lead to a host of problems, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease and death. Treatments followed the therapeutic philosophies in mode at the time, such as bloodletting or opium administration. Some 19th century physicians urged replenishment to reverse the wasting through aggressive feeding, even with sugar. As chemistry advanced and the role of carbohydrates in this process became better understood, a popular approach was to reduce carbohydrates while increasing fats to help fortify the patient, leading to a variety of fad diets. Physician Frederick Allen’s research in the late 19th and early 20th centuries contradicted that approach, focusing instead on a reduction of all food components to aim for an optimum point of malnourishment to sustain the diabetic. Allen’s research suggested that this therapy, which became known as “starvation treatment,” offered the best hope available for the patient. Yet it often came down to death by diabetes or death by starvation.

(National Library of Medicine)

Another approach to treating diabetes followed from physiological research and the nascence of endocrinology, when scientists identified links between internal secretions from different organs to various physiological functions. In the last third of the 19th century researchers connected pancreatic function to diabetes. With the suspect organ identified, many attempted to create pancreatic extracts to treat diabetes, in animal models and then clinically. Several reported limited success on both counts; one clinician claimed to temporarily bring a patient out of a diabetic coma. However, processing pancreatic tissue and its enzymes was extremely difficult and typically produced results too toxic to be of any practical use. Thus, by the early 20th century, as historian Michael Bliss dismally reported in The Discovery of Insulin, “the total dietary approach to diabetes was the best therapy available at that time. . . . diabetologists often wrote scornfully of the ignorance with which doctors treated diabetes—at worst with opium and over-feeding, at best by handing out printed, out-of-date diets. And even they were better than the patent medicine men who offered nostrums such as Bauer’s Antidiabeticum . . . .”

HEALTH FRAUD AND DIABETES

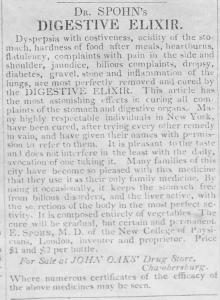

As a poorly understood disease that affected many for whom regular medicine offered very little in the way of effective therapeutics, diabetes provided a bounty for the unscrupulous who preyed on patients. Treatments for diabetics to self-medicate, like the patent medicines mentioned above, generally have been available for centuries in America. A 1756 ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette for Dr. William Cockburn’s Specific Medicine claimed to “infallibly cure . . . the diabetes, or want of power to keep one’s urine, tho’ of long standing.” A host of antebellum potions like the Elixir of Life of Rev. T. Bartholomew, M. D., Dr. E. Spohn’s Digestive Elixir that “most perfectly removed and cured” diabetes, Brandreth’s Vegetable Universal Pills, and J. W. Poland’s White Pine Compound were among the wide range of universally useless treatments—for diabetes and the other diseases they claimed to cure.

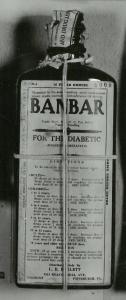

The 1906 Food and Drugs Act prohibited false, misleading, and fraudulent labels on drugs, leading to successful actions against several alleged diabetic treatments, such as the Fulton Diabetic Compound (on multiple occasions) and Warner’s Safe Diabetes Remedy, which was neither safe nor a remedy. The Post Office and the Federal Trade Commission also interceded in the distribution and advertising of certain diabetes remedies under their authorities, such as with Amber-ita (a real estate broker’s entry into the drug business), Carr’s Diabetic Treatment, and Diabeticine, which claimed the diabetic could “avoid future necessity of injecting insulin.” The latter is important to note, as many of these inert treatments came after insulin’s discovery. The maker of one of these, Banbar, challenged FDA’s seizure in court and won—having convinced the jury that he believed Banbar to work, and thus the label did not meet the fraud requirement under the law. The FDA featured Banbar in its early 1930s traveling display of dangerous and deceitful but technically legal products on the market and why a new law was so important.

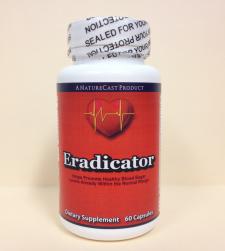

Finally, fraud in the management of diabetes is not something relegated to the distant past. For example, in the last decade FDA issued warning letters, advisories, and alerts for more than a dozen treatments for diabetes (https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/illegally-sold-diabetes-treatments). And in September 2021 FDA and FTC collaboratively drew the public’s attention to manufacturers of 10 dietary supplements that claimed to effectively manage diabetes, the FTC interceding with cease and desist orders.

|

|

|

|

|

THE DISCOVERY OF INSULIN

Frederick Banting was not the first to search for the anti-diabetic internal secretion of the pancreas—a quest that depended on both the birth of endocrinology itself as well as evidence that linked the organ to the disease. Even the term for this secretion, insulin, had been coined years before, despite the fact that it remained elusive. But his approach, determination, and the contributions of those who worked with him spelled the difference that benefited diabetics across the world. Neither Banting, a practicing physician who presented his plan to University of Toronto physiologist J. J. R. Macleod, nor the medical student assigned by Macleod to assist Banting, Charles Best, were experienced physiological researchers. Beginning their investigation in May 1921, their results from administering pancreatic extracts to diabetic animals showed promise. In December Macleod put visiting biochemist James B. Collip on the team. Collip substantially improved the purity of the extracts, and clinical studies by January 1922 demonstrated several signs of the extract’s positive impact, including reduction of the patient’s blood sugar. Interest in their work and requests for insulin had been growing even before Banting and Best’s first publication in February 1922.

The group planned to expand use of the extract in diabetic patients, but scaling up production in the university’s in-house labs proved problematical. Toronto engaged Eli Lilly and Company of Indianapolis for production assistance, the firm’s research director having previously broached the subject following the team’s presentation of their research at a scientific conference in December 1921. By May 1922 Toronto and Lilly reached an agreement for collaboration, and production grew enough due to Lilly’s engineering changes to expand the investigations to many clinics by the late Summer. The university and firm had disagreements, especially on extending an experimental period with limited distribution of insulin until the Fall of 1923, when Toronto allowed Lilly’s general distribution of the drug. But the experimental period had proven the value of insulin and changed the course of diabetes therapy forever.

|

|

|

|

|

THE 1941 INSULIN AMENDMENT

In the early 1920s the University of Toronto’s Insulin Committee, representing the university where insulin was discovered, received a U. S. patent for insulin and the method of its production. This gave them control over who would be able to manufacture the drug and how that would be done. The Committee required that each licensee assay and standardize every batch of medicine and submit a sample to Toronto for analysis there as well. No insulin could be released for sale without the Insulin Committee’s express approval. Given the life or death importance of insulin, strict control was necessary. However, this system would last only as long as the patent itself, and that was due to expire on December 24, 1941. In November 1941 officials from the FDA, the U. S. Pharmacopoeia, and other institutions met to discuss the development of USP insulin standards in anticipation of a move to have FDA continue an insulin certification program.

However, insulin was not a new drug under the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and thus not subject to premarket provisions of the law. And even if it were, there was no provision for pre-market, batch-by-batch certification for a drug (although that law authorized FDA to batch-certify coal-tar colors). On December 16th a bill to require FDA certification of insulin and concomitant regulations was introduced in Congress, and six days later—48 hours before the Toronto patent expired—the 1941 Insulin Amendment became law.

INNOVATIONS IN GLUCOSE TESTING DEVICES

For decades after the discovery and commercialization of insulin, diabetes treatment was constrained by the lack of an accurate and practical means of measuring blood glucose. It had been known since 1838 that glucose was the key sugar that patients with diabetes are unable to metabolize, and as of 1850 the first reagent strips were invented to detect the presence of glucose in urine. While these early reagent strips used stannous chloride (which turned black if glucose was present), by the early 1900s copper reagents emerged as the standard in urine glucose testing (and remained the dominant technology until the 1960s).

However, urine testing had several troubling limitations – perhaps most significantly, it was a relatively late physiological account of the patient’s glycemic status. Also, the accuracy of the results varied according to the patient’s fluid intake and the concentration of their urine. So, by the mid-20th century researchers sought a more sensitive method of glucose testing that relied on blood samples. In 1965 the Ames Research Division of Miles Laboratories developed Dextrostix, the first blood glucose test strip, which relied on dry-reagent chemistry to detect glucose. Dextrostix were paper strips pre-treated with the enzymes glucose oxidase and peroxidase. A patient would apply a rather large drop of blood to the reagent pad (approximately 50-100 μL), allow it to soak in for one minute then wipe it away to remove the red blood cells. If glucose was present, it would generate a chemical reaction that produced a color change that would be compared to a color-coded chart that indicated the blood glucose value. Such rapidly available results were a benefit to doctors’ offices and hospitals, however they were not meant for self-testing and fading of the colored charts affected their accuracy.

In 1970 Ames chemist Anton Clemens developed the first electronic meter meant for self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). The Ames Reflectance Meter (ARM) used a photoelectric cell to measure light reflected from the surface of a test strip, which was then displayed on an analog scale. It was a revolutionary advancement, but it was heavy and costly (at nearly $500). The lighter-weight and more compact and portable Ames Glucometer was emblematic of a second generation of blood glucose monitoring system (BGMS) introduced in the 1980s, which also introduced features such as countdown timers and auto calibration. In that decade reagent strips were also redesigned to require smaller quantities of blood, and by the end of the 1980s, enzyme electrode strips were introduced both to augment reflectance strips and to be used in newly developed and highly portable biosensor electrode meters.

In the 1990s BGMS further improved to reduce operator errors. It required even smaller amounts of blood and facilitated proper test timing and calibration, while also empowering patients with greater tools to monitor their glucose levels through enhanced memory capacity. It could store hundreds of tests and had meters capable of integrating with personal computing equipment. The introduction of continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMs) that used subcutaneous catheters to measure the glucose levels in interstitial fluid enabled patients to chart blood sugar fluctuations throughout the day rather than just at a few select times.

GENETICALLY-MODIFIED INSULIN

Since the 1920s insulin production required enormous quantities of animal pancreases, generally from cows or pigs. Advancements in chromatographic processing in the 1970s enabled firms to produce purer insulin, reducing the risk of the development of anti-insulin antibodies that had been found to induce insulin resistance in a significant number of patients. Yet, these techniques required even more glands per unit of insulin (IU). By 1981 production of one pound of insulin required 8,000 pounds of glands from 23,500 animals – but this was only enough insulin to treat 750 patients with diabetes for one year. Because insulin production was so fundamentally dependent on animal glands, both the supply and the cost of insulin depended on gland availability, and over the course of the 1970s the U.S. supply of pancreas glands declined significantly, while the cost of beef and pork fluctuated wildly. These market forces revealed the unsustainable nature of dependency on animal sources for insulin production.

The looming fear of an animal insulin shortages was eased by a revolutionary discovery that leveraged mid-1970s innovations involving gene-splicing. In 1978 scientists at City of Hope and Genentech developed a method for producing biosynthetic human insulin (BHI) using recombinant DNA technology in a unique multi-step process. After extracting and manipulating the two polypeptide chains, A and B, that make up the human insulin gene, they inserted these into a common bacteria, which they programmed genetically to produce large amounts of insulin. Eli Lilly & Co. signed an agreement with Genentech to use the rDNA method to make human insulin commercially available. On October 28, 1982, after only 5 months of review, the FDA approved Humulin, the first biosynthetic human insulin product and the first approved medical product of any kind that derived from this technology.

The development of BHIs not only promised to resolve the supply and price volatility inherent in the production of animal insulins, but also enabled the development of efficient manufacturing design and protocols to achieve even greater purity and standard adherence. Yet, perhaps more importantly, the introduction of synthetic insulin marked a paradigm shift in diabetes therapeutics that soon led to the development of other non-animal derived products, including fast-acting insulin analogs, such as Humalog (approved by FDA in 1996), and long-acting insulin analogs, such as Lantus (approved by FDA in 2000). This diversification of insulin products gave patients a wider range of therapeutic options and greater control over diabetes management. From the 1980s on, the market for insulin products increasingly focused on satisfying the therapeutic and lifestyle needs of diabetic patients, which led to the introduction of products such as insulin pens and inhalable insulin – some of which were more commercially successful than others, but all of which aimed to meet the diverse needs of diabetes patients.

SUNSETTING THE FDA INSULIN CERTIFICATION PROGRAM

In 1997, after 56 years of success, FDA’s insulin certification program came to an end with the passage of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA). In many ways, the repeal of the program was a reflection of its success. By the 1970s, the insulin certification program had achieved its original objective to ensure that products adhered to consistent quality and potency standards. As new insulin products were introduced to the market, the program continued to enforce high standards, and in doing so, bolster consumer confidence. Naturally, from the 1940s to the 1990s, scientific advancements produced more sensitive tests and assays, yet in order to adapt to these improvements, FDA was required to implement rulemaking procedures to update the insulin monograph. In the meantime, any discrepancy between the current FDA monograph and the USP standard generated confusion. Part of the impetus for disbanding FDA’s certification program was to enable the agency to enforce the USP standards without requiring rulemaking procedures each time there was an assay or test was improved.

At the same time, Vice President Al Gore’s Reinventing Government initiative strove to reduce “unnecessary” regulatory programs. Through a program of “performance review reports,” the administration elicited feedback from executive agencies about potentially expendable programs, and in April 1995 FDA contributed several suggestions to reinvent regulation of drugs and medical devices. In this context, eliminating the insulin certification program seemed a common-sense solution given the high quality of the insulin supply and the challenge of keeping pace with the USP’s advancing standards.

BIOSIMILAR INSULIN

In the 25 years since FDA’s insulin certification program ceased, the insulin marketplace has changed significantly. Perhaps the greatest concern throughout this time period has been the need to remove financial barriers to insulin access. To resolve this conundrum, in 2009 Congress passed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act which created a 10-year timeline to transition to a new regulatory pathway that would allow for the introduction of biosimilar biologics and the regulation of insulin as a biologic not a drug. Biosimilar products use similar manufacturing processes to produce products that have no clinically meaningful difference in terms of safety, purity or potency from their reference product. Interchangeable biosimilars are approved to be switched or alternated with a reference product based on data demonstrating such use does not pose increased risk of immunogenicity compared with only using the reference product. On March 23, 2020 FDA began receiving applications for biosimilar products, including insulin, and on July 29, 2021 the agency approved the first interchangeable biosimilar insulin product, Semglee, indicated to improve glycemic control in adults and pediatric patients with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The approval of Mylan Pharmaceutical’s Semglee (insulin glargine-yfgn) provided a lower-cost option to the reference product Lantus (insulin glargine), a long-acting insulin analog. Acting Commissioner of Food and Drugs Janet Woodcock noted the approval of Semglee “furthers FDA’s longstanding commitment to support a competitive marketplace for biological products and ultimately empowers patients by helping to increase access to safe, effective and high-quality medications at potentially lower-costs.”