Alma LeVant Hayden's Contributions to Regulatory Science

Alma Hayden, 1952 (Photo Credit: Office of NIH History)

A remarkable but unsung leader, Alma LeVant Hayden played a pivotal role in advancing FDA's drug analysis capabilities in the 1950s and 1960s. An expert in spectrophotometry and chromatography, she helped to implement these techniques in FDA's drug review and enforcement work, modernizing the agency's scientific techniques at a critical time in the agency's growth and amidst revolutionary changes in federal drug regulation. As the head of the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry's Spectrophotometry Branch, she led the analysis of a notorious quack cancer product, which produced evidence that it was fraudulent, and she later testified for the FDA in the criminal trial against the drug's proprietors. Alma Hayden was an exemplary regulatory scientist who had a powerful impact on the agency's ability to protect and promote public health.

Discovering a Passion for Chemistry

Alma Jerlene LeVant Hayden was born in Greenville, South Carolina on March 30, 1927. She attended South Carolina State College (now University), an historically black college in Orangeburg, S.C., and graduated with honors in 1947. Initially Alma thought she wanted to be a nurse, however after studying chemistry in college she discovered “she just didn’t want to part from it.”1 So, she pursued graduate studies at Howard University where she studied various methods of chemical analysis under the eminent Lloyd Noel Ferguson (who became renowned for his pioneering work on the chemistry of taste and advancement of STEM opportunities for students of color) and received a grant from the Office of Naval Research for her research on The Electrolytic Oxidation and Reduction of Some Pyridine Compounds. After completing her master’s thesis in June of 1949, Alma worked as Ferguson’s research associate at Howard for two years, honing expertise in infrared spectroscopy.2

National Institute of Arthritic and Metabolic Diseases

In 1951, Alma took a position at the National Institute of Arthritic and Metabolic Diseases as an organic chemist and later a steroid chemist, where she used cutting edge methods to analyze organic substances and synthetic analogs. For instance, in the photograph at the right Alma is demonstrating how the newly developed technique paper chromatography can be used to identify steroids. Drops of liquid containing the substance under study have been placed on porous paper and allowed time to absorb vertically through the paper which Alma is spraying with a reagent. Because different substances will absorb and move through the paper at different speeds and generate different colored marks when sprayed with the reagent, researchers are able to ascertain certain essential qualities, such as mass, to identify the chemical. This photograph was taken in 1952, the same year that the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to the discoverers of paper chromatography, Archer John Porter Martin and Richard Laurence Millington Synge. At that point the science of paper chromatography had only been in use for 8 years and but was already revolutionizing various aspects of chemical analysis, including the identification of pharmaceutical substances and food adulterants.

Innovations in Spectroscopy

Alma’s work in paper chromatography was but one emerging analytical method that she applied to help advance federal scientific research. She also became a nationally recognized expert in another recently discovered technique of chemical analysis called spectrophotometry which visualizes the electromagnetic radiation absorbed by substances using specialized equipment that can measure and graph the wavelengths of light absorbed by a substance.3 Because substance will absorb a unique spectrum of radiation, this technique can be used to determine the chemical identity or “fingerprint” of a substance and can identify an unknown entity by matching the spectrophotometric tracing to those of known substances. When Arnold J. Beckman of National Technical Laboratories invented this method in 1940, the chemical analysis process was transformed from a weeks-long venture yielding only 25% accuracy to one that took only a few minutes and yielded 99.99% accuracy. FDA did not obtain an inhouse infrared spectrophotometer until 1947, but by the mid-1950s, spectrophotometry and chromatography were the two most important “mainstays of the modern drug laboratory,” and Alma Hayden’s expertise in these methods were a major advantage to in the agency’s work in analytical drug chemistry.4

Advancing Drug Analysis at FDA

In 1956 Alma began working as an analytical chemist in FDA’s Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry. Her expertise in infrared spectroscopy was invaluable in pharmaceutical analysis and identifying adulterants. By the early 1960s she had published 17 papers mostly on various aspects of infrared spectroscopy, including the absorption spectra of U.S. Pharmacopeial standards, as well as techniques for identifying steroids, barbiturates and sulfonamides. In May of 1963 she was named director of the Spectrophotometry Branch. About 6 months earlier, Congress passed the 1962 Drug Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, enacting significant reforms in federal drug regulation that would transform the conduct of clinical research and impose a stricter standard to be marketed in the U.S. by requiring drugs provide evidence of efficacy (as well as safety). In addition, drug sponsors would be required to submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) Application, as they had since 1938, but now under the explicit authorization of FDA to conduct clinical research to determine drug efficacy. One particular IND application filed immediately following the passage of these Amendments created “a profound feeling of skepticism about the manufacturing process and the conditions of distribution and use set forth in the Investigational New Drug Application.”5 The product, Krebiozen, would launch a major FDA investigation that would depend considerably on Alma Hayden’s expertise.

The Krebiozen Case

Krebiozen was first introduced in the U.S. in 1950 by Yugoslavian emigres Steven and Marco Durovic who claimed to have developed this alleged cancer cure from a serum derived from horse blood that was meant to induce natural tumor resistance. The product was endorsed by acclaimed cancer researcher Dr. Andrew Ivy (executive director of the National Advisory Cancer Council from 1947-1951 and author of the Nuremberg Code of ethics for human experimentation), who’s esteemed reputation lent an aura of legitimacy to this mysterious product. By the early 1960s, thousands of patients had been treated with Krebiozen injections, paying $9.50 per ampule (or about $87/treatment in 2021 USD). Krebiozen was both extremely popular and extremely profitable. However, despite amassing a vast number of passionate believers, the product lacked clinical evidence of any anti-cancer properties. In fact, in 1961 the proprietors of Krebiozen had discussed conducting a joint study of the drug with the National Cancer Institute (NCI), but were unable to reach an agreement about the appropriate research methods to pursue it.

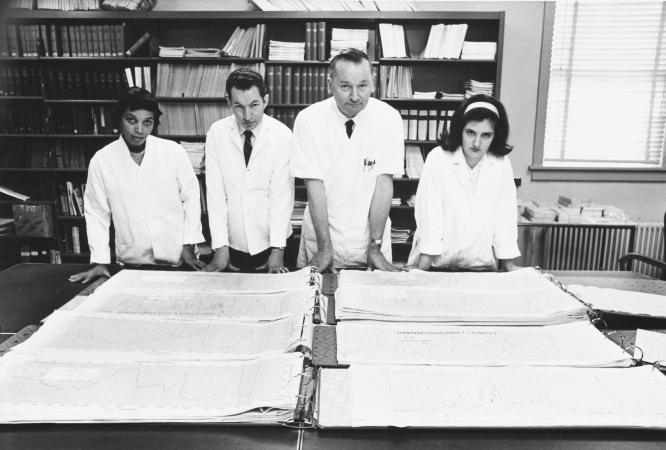

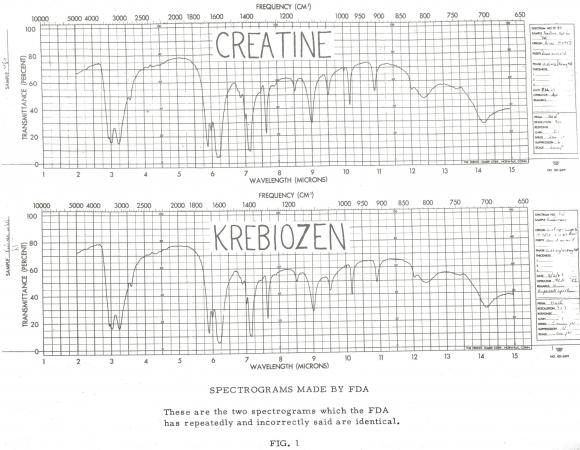

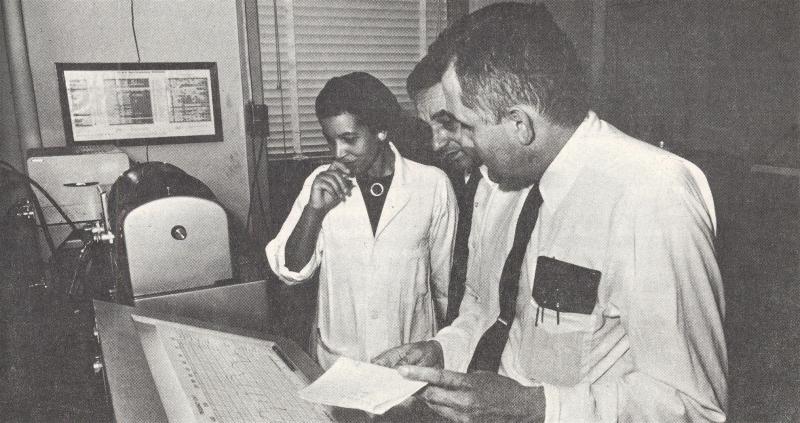

Leading FDA's In-House Analysis

When FDA launched its investigation of Krebiozen in 1962, it was able to obtain a sample and an infrared spectrum of the product from NCI. After repeated requests, Durovic also supplied 1 gram of Krebiozen to the agency. Having recently been named head of the Spectrophotometric Branch, Alma Hayden led the team that analyzed the samples of Krebiozen using infrared spectrophotometry. Both tracings suggested the sample included an amino acid present in blood. Hayden directed a summer student named Ruth Kessler to sort through a library of 20,000 chemical chromatograms to identify a potential match to the Krebiozen sample. Thankfully she found a match towards the beginning of the alphabet: creatine. The mystery ingredient in Krebiozen was nothing more than animal protein.

Extramural Analysis

To corroborate the Hayden’s team’s findings, FDA had multiple external analyses utilizing a variety of methods conducted by academic researchers across the country and NCI. Each study used either x-ray diffraction, mass spectrometry, microscopic crystallography, thin layer and paper chromatography, and behavior on melting. Each study confirmed that the sample was either creatine or creatinine (the latter a physiological by-product of the former). Associate Director of NCI, Dr. T. Philip Waalkes, whose staff had recently concluded a review of 500 Krebiozen case histories, said it is “impossible to conceive how minute doses of creatine could be of any value in treating cancer.”6

Testifying at the Trial

The FDA used these multiple studies to build a case against the Durovics and Ivy, who were indicted for 49 separate counts of violating federal drug regulations, including marketing an unapproved drug, violating IND regulations, making false statements to the FDA, adulteration and fraud. The case was extremely controversial due to the vast populist support of patients and families who falsely believed Krebiozen could cure cancer. It finally went to trial in April 1965 and lasted until January 1966, hearing testimony from 179 witnesses and producing 20,000 pages of official record. Alma Hayden was one of several witnesses who testified to the chemical identification of Krebiozen, making an irrefutable case that the substance was in fact creatine.7 However, the defense exploited the jury’s lack of scientific expertise and sowed doubt regarding the precision of the methods used. Shockingly, the jury ultimately acquitted the defendants, though several years later it became evident that at least one juror was influenced by pro-Krebiozen propaganda during the trial (for which he was jailed for contempt).

Legacy

Alma Hayden’s role in the Krebiozen investigation and trial were but a moment in her momentous career. However, this episode highlights both her scientific talent and her valorous public service. She applied her expertise in the identification of organic chemicals to advance public health and help ensure that patients are not exploited by ineffective “cures.” Two months after the trial concluded, Deputy Director of Scientific Research Daniel Banes reflected on the integral work of FDA scientists in the pursuit of justice, noting that “our scientists are oriented toward law enforcement, and our enforcement officers are science-oriented.”8 Having fought to protect the American public from a fake cancer cure, it is a terrible tragedy that Alma Hayden passed away the following year at the age of 40 after losing her own battle with cancer. Her contributions to organic chemistry and regulatory science are an enduring testament to her extraordinary abilities and impact.

- 1Report of World of Work Conference on Career and Job Opportunities : held at Howard University, Washington, D.C., July 26-28, 1962 / sponsors, Women's Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor, National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, Howard University (p. 22): https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112079572084&view=1up&seq=22&skin=2021&q1=hayden

- 2Alma J. LeVant and Lloyd N. Ferguson, "Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis of Mixtures of Bromochlorobenzenes," Journal of Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 23 (1951): 1510.

- 3Report of World of Work Conference on Career and Job Opportunities : held at Howard University, Washington, D.C., July 26-28, 1962 / sponsors, Women's Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor, National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, Howard University (p. 22): https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112079572084&view=1up&seq=22&skin=2021&q1=hayden

- 4Daniel Banes (Director of Scientific Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration) Oral History, Jun. 17, 1980, FDA Oral History Collection: https://www.fda.gov/media/81185/download

- 5Daniel Banes (Deputy Director of Scientific Research), “Some Scientific Aspects of the Kerbiozen Case,” Interbureau By-Lines, No. 5 (March 1966).

- 6“FDA Cracks ‘Krebiozen Code’,” F-D-C Reports: Drugs and Cosmetics, Vol. 25, No. 36 (Sept. 9, 1963): 19.

- 7She was also noted as the lead government scientist when the case was reviewed by Congress. See Congressional Record 12/6/1963 (p. 46): file:///C:/Users/Vanessa.Burrows/Downloads/GPO-CRECB-1963-pt18-3.pdf

- 8Daniel Banes (Deputy Director of Scientific Research), “Some Scientific Aspects of the Krebiozen Case,” Interbureau By-Lines, No. 5 (March 1966).