The Cattle Estrous Cycle and FDA-Approved Animal Drugs to Control and Synchronize Estrus—A Resource for Producers

On this page:

- Normal Estrous Cycle in Cattle

- Estrous Control and Synchrony in Cattle

- Benefits of FDA-Approved Animal Drugs

- Extra-Label Drug Use Not Allowed for Estrous Control and Synchrony in Cattle

- Resources for You

With only a one letter difference, the words “estrous” and “estrus” look and sound similar, but there’s an important difference. Estrus is a noun and refers to the short period in which a cow is sexually receptive and will stand to be bred. Estrus is commonly called “heat.” Estrous is an adjective used to describe things related to estrus, such as the behaviors associated with estrus (estrous behaviors) or the period from one estrus to the next (estrous cycle).

Normal Estrous Cycle in Cattle

A good understanding of the normal estrous cycle in cattle can help producers address reproductive challenges in both heifers (young female dairy or beef animals that have not yet had their first calf) and cows (female dairy or beef animals that have had at least one calf). This understanding is also critical when using a drug regimen to control and synchronize estrous cycles in cattle.

A heifer has her first estrus, or heat, at puberty. The age at puberty is influenced by genetics, nutrition, and body weight. Heifers fed an appropriate diet will generally reach puberty between 9 and 15 months of age. Dairy heifers tend to reach puberty earlier, at 9 to 12 months, whereas beef heifers tend to reach it a bit later, at 13 to 15 months. The age at puberty for some cattle breeds, such as Brahman, can be as late as 24 months.

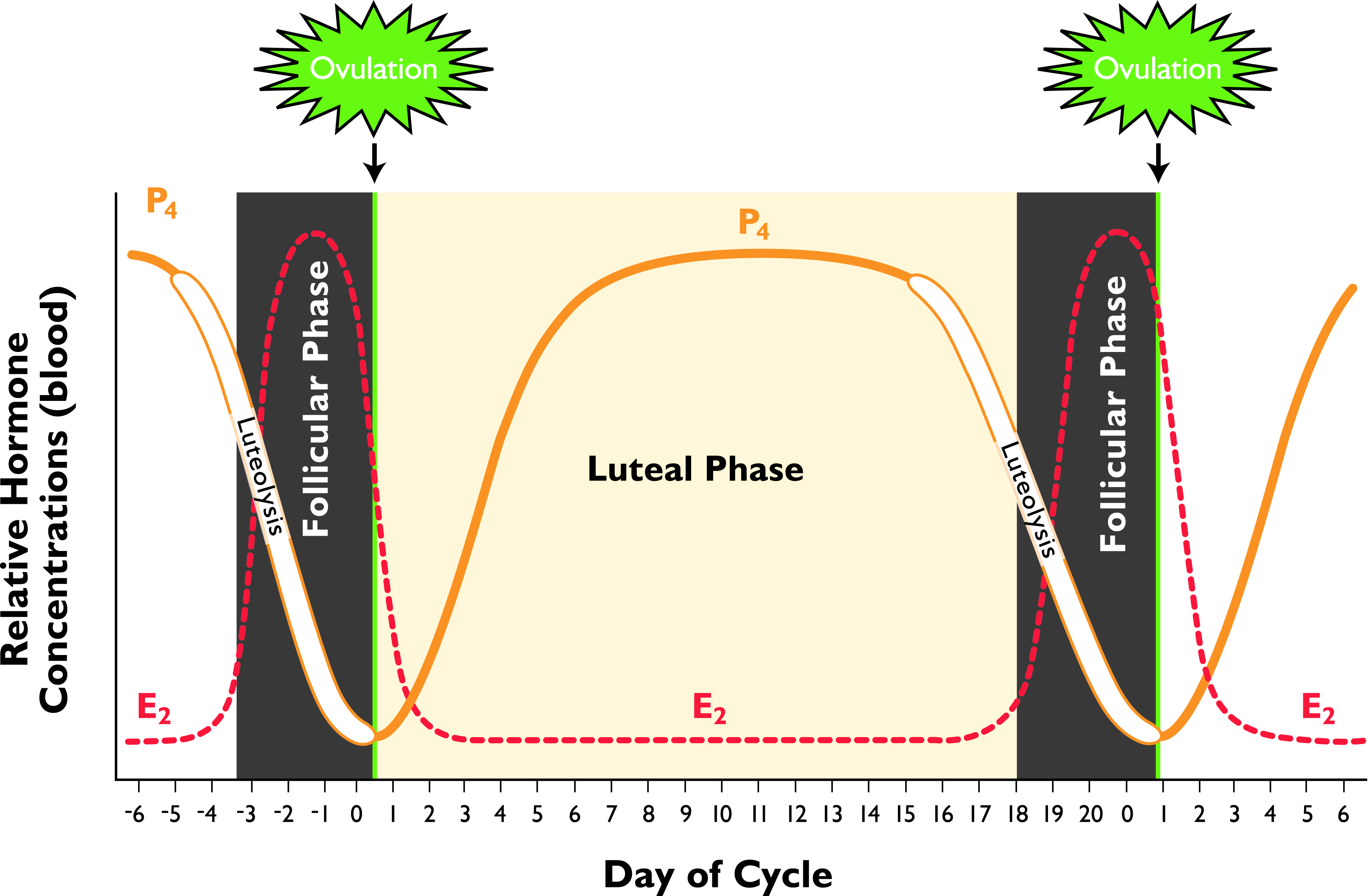

After puberty, a heifer continues to have regular estrous cycles every 21 days (the normal range is every 18 to 24 days). The estrous cycle in cattle is complex and regulated by several hormones and organs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 —Phases of the bovine estrous cycle. Note: E2 = estrogen and P4 = progesterone. (Figure used with permission from Current Conceptions, Inc. from Pathways to Pregnancy and Parturition, 3rd ed.1 Image cannot be reprinted in any other publication in hard copy or electronic form without written permission from Current Conceptions, Inc.)

The Follicular Phase: Waves of Ovarian Follicles

The follicular phase of the estrous cycle refers to the narrow period of time right before estrus (heat) and ovulation (release of the egg for possible fertilization). During this phase, there is rapid growth of a dominant ovarian follicle and increased estrogen production.

A follicle is a structure containing an egg, also called an ovum, and other cells that can produce estrogen. A heifer or cow will generally have two or three groups of ovarian follicles—called waves—develop during a single estrous cycle (the range is one to four waves). One follicle in each wave will become the dominant follicle. Early in the estrous cycle, when the progesterone level is high, the dominant follicle will not ovulate. Instead, it will regress and allow another wave of follicles to emerge. The last wave occurs later in the estrous cycle when the progesterone level is low. The follicle that emerges as dominant during this wave will not regress. Instead, it will grow larger and produce increasingly more estrogen.

Estrus (Heat) and Ovulation

The high estrogen level produced by the dominant ovarian follicle causes the heifer or cow to show signs of estrus. This means she’s sexually receptive—she’s said to be “in heat”—and will stand to be bred or mounted by other cows, commonly referred to as “standing heat.” The heifer or cow may show other signs of estrus, such as having a clear mucous vaginal discharge and an increased activity level. She may also vocalize more and try to mount other cows. Estrus is considered the beginning, or “Day 0,” of the estrous cycle.

Besides causing the heifer or cow to show signs of estrus, the high level of estrogen produced by the dominant ovarian follicle also triggers the hypothalamus—a section of the brain—to release a surge of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) right before ovulation. GnRH causes the pituitary gland in the brain to release two other hormones—follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)—which travel in the blood to the ovary to control what happens to the follicles.

FSH is secreted during and shortly after estrus and causes a new wave of ovarian follicles to develop. A surge of LH causes the dominant ovarian follicle to rupture approximately 24 to 32 hours later, thus releasing the egg. This is ovulation and marks the transition from the follicular phase to the luteal phase.

The Luteal Phase: The Developing Corpus Luteum

During the luteal phase of the estrous cycle, the remnants of the newly ruptured ovarian follicle develop into the corpus luteum and begin to produce progesterone, a steroid hormone needed to support and maintain a potential pregnancy if the egg is fertilized. Over the first 10 days of the estrous cycle, the corpus luteum matures and increases in size. The corpus luteum reaches its maximum size and produces the most progesterone at mid-cycle (around Days 9 and 10). Under the influence of high progesterone, waves of follicles continue to emerge and regress without a dominant ovarian follicle rupturing. A dominant follicle won’t rupture again until the progesterone level falls during the next follicular phase.

No Pregnancy

If the egg isn’t fertilized or the early embryo fails to develop, the uterus releases the hormone prostaglandin F2-alpha around Days 16 to 20 of the estrous cycle. Prostaglandin F2-alpha causes the corpus luteum to regress. This is called luteolysis and leads to a drop in progesterone.

The low progesterone environment allows the dominant ovarian follicle to emerge from the last wave of follicles and mature instead of regress. The dominant follicle produces enough estrogen to cause estrus, thus starting the next estrous cycle.

Pregnancy

If the heifer or cow becomes pregnant, the embryo prevents the uterus from releasing prostaglandin F2-alpha and the corpus luteum continues to release progesterone. The high progesterone level stops the heifer or cow from cycling—she won’t go into heat or ovulate. In a normal, healthy pregnancy, the embryo develops into a fetus. Gestation (the period between when the animal becomes pregnant and when she calves) lasts about 283 days. It’s desirable for a heifer to have her first calf when she’s 2-years-old. For that to happen, the heifer must reach puberty and become pregnant by 14 to 15 months of age.

Cyclicity

When a heifer or cow has an estrous cycle that’s normal in length and she displays normal estrous behaviors during heat, she’s said to be "cycling." When a heifer or cow isn’t pregnant but she’s not ovulating or showing signs of heat, she’s not cycling. Instead, she's "anestrus," which is sometimes described as being “acyclic.” Right after a heifer or cow calves, it’s normal for her to be anestrus for a short period of time. Sometimes a medical problem, such as ovarian cysts or an infection of the reproductive tract, can cause a cow to stop cycling. Another reproductive challenge is silent heat—when a heifer or cow appears to be anestrus but, in fact, she is cycling normally and just not showing signs of heat.

Estrous Control and Synchrony in Cattle

Exogenous hormones can mimic the hormones of the natural estrous cycle in cattle. By administering exogenous hormones, producers can control and synchronize estrus in breeding heifers and cows as well as shorten their estrous cycles. Producers can group animals according to the phase of their estrous cycle, which reduces management burdens. Some estrous synchrony regimens may also induce or advance estrus in animals that aren’t cycling (they’re anestrus). For example, a cow is normally anestrus after giving birth, and an estrous synchrony regimen may be used to advance her first heat after calving. This allows her to be bred again sooner. These drug regimens may also be used to advance the timing of the first heat in heifers at puberty.

Some FDA-approved animal drugs are available for use in estrous control and synchrony regimens for cattle (see Table 1). These regimens use three classes of drugs:

- Drugs in the gonadorelin class act similar to gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) naturally released from the hypothalamus during the estrous cycle. These drugs mimic the surge of GnRH right before ovulation to cause the animal’s pituitary gland to secrete FSH and LH. As described above, FSH causes a new wave of ovarian follicles to develop, and LH causes the dominant follicle to rupture and release the egg (ovulation).

Five gonadorelin products are FDA-approved to treat ovarian cysts, which is a therapeutic use. (A therapeutic use means the drug is used to treat, control, or prevent disease.) Four of the five gonadorelin products are also FDA-approved to control or synchronize estrous cycles in cattle when given sequentially with another drug (see Table 1). Estrous control and synchrony are not therapeutic uses. All five gonadorelin products are prescription only.

- Drugs in the progestin class act similar to the hormone progesterone naturally secreted by the corpus luteum. These drugs can supplement the progesterone level in the heifer’s or cow’s body to:

- Influence the release of FSH and LH from the pituitary gland;

- Suppress estrus (heat); and

- Block ovulation.

Only one progestin, an over-the-counter intravaginal insert, is FDA-approved for synchronizing estrous cycles or advancing estrus in cattle either when given alone or sequentially with another drug (see Table 1). Melengestrol acetate, another progestin, is FDA-approved for use in manufacturing medicated feed to suppress estrus in heifers but is not approved for synchronizing estrous cycles or advancing estrus in cows or heifers.

- Drugs in the prostaglandin class act similar to the hormone prostaglandin F2-alpha naturally released from the uterus when there is no pregnancy. These drugs cause luteolysis—the regression of the corpus luteum if it’s mature enough to respond to the effects of prostaglandin F2-alpha. After the corpus luteum regresses, a new dominant ovarian follicle emerges and ruptures, causing ovulation and a new estrous cycle to start. Using prostaglandin drugs in the first 5 days of the estrous cycle won’t cause the corpus luteum to regress because the early corpus luteum is immature and doesn’t respond to prostaglandin F2-alpha.

Five prostaglandin products are FDA-approved for several therapeutic uses. All five products are also approved for estrous synchrony in a single- or double-injection prostaglandin-only regimen. Four of these products are also FDA-approved for sequential use with another drug to synchronize estrous cycles or advance estrus in cattle (see Table 1). All five prostaglandin products are prescription only.

Except as described in the various regimens listed in the table below, it’s illegal to use any of these drugs with another drug for estrous control and synchrony in cattle. Before using any drug, it’s important to read the labeling to make sure the drug is approved for the intended use and to follow the directions for use. Prescription animal drugs must be used by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian.

Table 1—Available FDA-Approved Drugs to Control and Synchronize Estrous Cycles in Cattle (see Animal Drugs @ FDA for specific information about each drug).

| Regimen | Drug Name (Established Name, also called Active Ingredient) |

Application Number and Manufacturer | Sequential Use with Another Drug |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gonadorelin-Prostaglandin | Factrel® Injection (gonadorelin injection) |

NADAa 139-237 Zoetis Inc. |

Lutalyse® Injection or Lutalyse® HighCon Injection |

| Fertagyl® (gonadorelin) |

ANADAb 200-134 Intervet, Inc. |

Estrumate® | |

| GONAbreed® (gonadorelin acetate) |

ANADA 200-541 Parnell Technologies Pty. Ltd. |

cloprostenol sodium | |

| CYSTORELIN® (gonadorelin) |

NADA 098-379 Merial, Inc. |

cloprostenol sodium | |

| Progestin-only | EAZI-BREED™ CIDR® (progesterone intravaginal insert) |

NADA 141-200 Zoetis Inc. |

None |

| Progestin-Prostaglandin | EAZI-BREED™ CIDR® (progesterone intravaginal insert) |

NADA 141-200 Zoetis Inc. |

Lutalyse® Injection or Lutalyse® HighCon Injection |

| Prostaglandin-only |

Lutalyse® Injection & Lutalyse® HighCon Injection (dinoprost tromethamine injection) |

NADA 108-901 & NADA 141-442 Zoetis Inc. |

None |

| Estrumate® (cloprostenol injection) |

NADA 113-645 Intervet, Inc. |

None | |

| ProstaMate™ (dinoprost tromethamine) |

ANADA 200-253 Bimeda Animal Health Limited |

None | |

| estroPLAN® (cloprostenol sodium) |

ANADA 200-310 Parnell Technologies Pty. Ltd. |

None |

b Abbreviated New Animal Drug Application

Note: Some of the above drugs may be marketed with a different trade name (also known as the proprietary name) under what’s called “distributor labeling.”

Benefits of FDA-Approved Animal Drugs

FDA rigorously evaluates an animal drug before approving it. As part of the approval process, the drug company must prove to FDA that:

- The drug is safe and effective for a specific use in a specific animal species. For a drug intended for use in food-producing animals, the company must also prove that food made from animals treated with the drug is safe for people to eat;

- The manufacturing process is adequate to preserve the drug’s identity, strength, quality, and purity. The company must show that the drug can be consistently produced from batch to batch; and

- The drug’s labeling is truthful, complete, and not misleading. The company must make sure that the labeling contains all necessary information to use the drug safely and effectively and includes the risks associated with the drug.

FDA’s role does not stop after the agency approves an animal drug. As long as the drug company markets the animal drug, the agency continues to monitor:

- The drug’s safety and effectiveness. Sometimes, the agency’s post-approval monitoring uncovers safety and effectiveness issues that were unknown at the time of approval;

- The manufacturing process to ensure quality and consistency are maintained from batch to batch;

- The drug’s labeling to make sure the information remains truthful, complete, and not misleading; and

- The company’s marketing communications related to the drug to make sure the information is truthful and not misleading.

Extra-Label Drug Use Not Allowed for Estrous Control and Synchrony in Cattle

Under specified conditions, veterinarians are legally allowed to prescribe approved human and animal drugs for extra-label uses in animals. When an approved human or animal drug is used in a way other than what is stated on the drug’s labeling, it’s an extra-label use. This is commonly called “off-label” use because the drug is used in a way that’s “off the label.”

Veterinarians must follow FDA’s requirements for extra-label drug use in animals, as stated in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and FDA regulations. Using a drug in an extra-label manner for estrous control and synchrony doesn't comply with these requirements, which state that for food-producing animals, a veterinarian must carefully diagnose a medical condition and any drug he or she prescribes in an extra-label manner must be for a therapeutic use (to treat, control, or prevent a disease). Estrous control and synchrony are not therapeutic uses.

Resources for You

- Letters to Bovine Veterinarians

- The Estrous Cycle of Cattle, Mississippi State University Extension

- Back to the Basics: Explaining the Estrous Cycle, Dairy Cattle Reproduction Council

- Estrous Cycle Learning Module, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, George Perry, Extension Beef Reproduction Management Specialist

ENDNOTE

1 Senger PL. Pathways to pregnancy and parturition. 3rd ed. Pullman, WA: Current Conceptions, Inc., 2012;144.