Strategic Plan for Risk Communication

Printer-friendly PDF (259.8KB)

FDA’s Strategic Plan for Risk Communication

Fall 2009

2012 Update- see Appendix II below

Printer-friendly PDF of Appendix II (92KB)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Food and Drug Administration

Table of Contents

FDA Risk Communication Strategic Plan at a Glance

The Strategic Plan — The Evolving Role of FDA Risk Communication

Defining Risk Communication for the Future

- Risk Communication Is Science-Based

- Risk–Benefit Information Provides Context and Is Adapted to Audience Needs

- FDA’s Approach to Risk Communication Is Results-Oriented

- Strengthen the Science That Supports Effective Risk Communication

- Expand FDA Capacity to Generate, Disseminate, and Oversee Effective Risk Communication

- Optimize FDA Policies on Communicating Risks and Benefits

Appendix: Goals, Strategies and Associated Actions

Purpose

The purpose of this document is to describe the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s strategy for improving how the agency communicates about regulated products. The strategy is intended to guide program development and research planning in a dynamic environment where rapidly evolving technologies enable patients and consumers to become increasingly involved in managing their health and well-being. We define three key areas—science, capacity, and policy—in which strategic actions can help improve how we communicate about the risks and benefits of regulated products, as well as how we oversee communications produced by regulated entities. The box titled FDA Risk Communication Strategic Plan at a Glance(see page 4)summarizes the three key areas and the associated strategies on which we will focus our efforts. This FDA Strategic Plan for Risk Communication is an ambitious one that will take time and substantial collaboration with stakeholders to implement. However, FDA is confident this strategy will help ensure that FDA-regulated products are used appropriately, a goal critical to the agency’s mission of protecting and promoting the public health.

Background

FDA recognizes the importance of communicating effectively about FDA-regulated products to achieve its mission of protecting and promoting the public health. Effective communication supports both optimal use of medical products and safe consumption of foods to maximize health. FDA’s job is to “minimize risks through education, regulation, and enforcement,” and it must do this by communicating “frequently and clearly about risks and benefits—and about what organizations and individuals can do to minimize risk.”1

In 1999, FDA released a report that acknowledged risk communication as a key component in the effective management of medical product risks.2 In 2006, FDA asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to investigate the agency’s drug safety efforts and to recommend improvements to its existing systems. In response, the IOM produced the report The Future of Drug Safety: Promoting and Protecting the Health of the Public, which it released on September 22, 2006.3 Although the report focused on drug safety, it highlighted communication more generally, referencing FDA’s mission of “helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need…”4 and recommending the formation of an advisory committee on communication (IOM Recommendation 6.1). More recently, FDA’s Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner asserted that “one of the greatest challenges facing any public health agency is that of risk communication.”1

Although the IOM’s recommendation to create a communications-focused advisory committee was directed to Congress and focused primarily on medical products, FDA independently responded by launching its Risk Communication Advisory Committee in 2007. This Advisory Committee provides advice on how best to communicate with the public about the risks and benefits of FDA-regulated products to facilitate optimal use of these products. The Advisory Committee was established to help FDA improve its communication policies and practices, review and evaluate relevant research, and help to implement communication strategies consistent with the most current knowledge.5

At the Advisory Committee’s August 2008 meeting, members voted unanimously to accept two resolutions:

- FDA should consider risk communication as a strategic function, to be considered in designing FDA core processes.

- FDA should engage in strategic planning of its risk communication activities.

To that end, FDA has developed a Strategic Plan for Risk Communication, which is described in this document. FDA has the capacity to empower the public by providing healthcare professionals, patients, and consumers with the information they need about FDA-regulated products, in the form they need it, when they need it. The plan presents FDA’s strategies for risk communication and proposes ways to improve FDA’s science base, its capacity for action, and its policy processes. FDA takes the approach that risk communication:

- is integral to carrying out FDA’s mission effectively;

- is a two-way process;

- must be adapted to the various needs of the parties involved; and

- must be evaluated to ensure optimal effectiveness.

Overview

The following Strategic Plan lays out FDA’s role in communicating the risks of regulated product use, defining risk communication anew for a 21st century in which evolving technologies have enabled increased patient and consumer involvement in managing their health and well-being. The document defines the three key areas (science, capacity, and policy) in which strategic actions, in collaboration with relevant domestic and international stakeholders, can improve the generation, dissemination, and regulation of risk communication about regulated products. It also identifies and details 14 specific strategies.

FDA is showing its commitment to the goals of the plan not just by identifying the strategies it will implement, but also by identifying over 70 actions the agency plans to take within the next few years to improve risk communication. The document also identifies 14 of those actions that FDA plans to accomplish within the next 12 months. Chief among these are the following two actions.

- Identify outcomes and develop measures for assessing progress toward goals and strategies

- Develop detailed action plans at agency and Center levels for determining time frames and resources to achieve proposed action steps, and coordinating budget needs through the annual budget process

FDA Risk Communication Strategic Plan at a Glance

Strengthen the science that supports effective risk communication

Science Strategy 1: Identify gaps in key areas of risk communication knowledge and implementation and work toward filling those gaps

Science Strategy 2: Evaluate the effectiveness of FDA’s risk communication and related activities and monitor those of other stakeholders

Science Strategy 3: Translate and integrate knowledge gained through research/evaluation into practice

Expand FDA capacity to generate, disseminate, and oversee effective risk communication

Capacity Strategy 1: Streamline and more effectively coordinate the development of communication messages and activities

Capacity Strategy 2: Plan for crisis communications

Capacity Strategy 3: Streamline processes for conducting communication research and testing, including evaluation

Capacity Strategy 4: Clarify roles and responsibilities of staff involved in drafting, reviewing, testing, and clearing messages

Capacity Strategy 5: Increase staff with decision and behavioral science expertise and involve them in communication design and message development

Capacity Strategy 6: Improve the effectiveness of FDA’s Web site and Web tools as primary mechanisms for communicating with different stakeholders

Capacity Strategy 7: Improve two-way communication and dissemination through enhanced partnering with government and nongovernment organizations

Optimize FDA policies on communicating risks and benefits

Policy Strategy 1: Develop principles to guide consistent and easily understood FDA communications

Policy Strategy 2: Identify consistent criteria for when and how to communicate emerging risk information

Policy Strategy 3: Re-evaluate and optimize policies for engaging with partners to facilitate effective communication about regulated products

Policy Strategy 4: Assess and improve FDA communication policies in areas of high public health impact

The Strategic Plan — The Evolving Role of FDA Risk Communication

FDA’s responsibilities have increased greatly in recent years, as globalization, emerging areas of science, evolving technologies, and people’s growing interest in managing their health and well-being present the agency with unprecedented challenges and opportunities. These factors have enormous implications for how the agency communicates the risks and benefits of the products it regulates.

In the past, FDA’s communication efforts were largely restricted to overseeing the key vehicle for communicating risk information to the public—the labeling of FDA-regulated products. The process of negotiating with product manufacturers about changes to labeling or decisions to recall a product was often lengthy. Now, as the Internet and emerging technologies both enable and feed the public’s demand for greater transparency and communication frequency, these protracted waiting periods are giving way to communication in real time. Thus, designing a contemporary risk communication strategy is critical to FDA’s efforts to realize its potential for effective protection and promotion of health, enabled by 21st century knowledge and technology.

Communicating the appropriate use of FDA-regulated products is crucial

An important facet of FDA’s risk communication strategy and mission has always been educating the public about the appropriate use of FDA-regulated products. The public, however, consists of a variety of audiences throughout the world, including healthcare professionals who prescribe and administer medical products, their patients, and consumers who choose nonprescription products, foods, and products for animals. Today, we recognize that education involves more than ensuring the accuracy of product labeling; we must communicate the context of the message so that the words make sense to the audience. For example, in reviewing certain medical product marketing applications, FDA determines that a product is safe and effective. But that decision is made within a specific legal context, which is that the product meets the legal standard of safe and effective for its labeled or intended use—to read either word as an absolute would be misleading. It remains unknown whether the public—healthcare professionals, consumers, patients, patients’ caregivers, and even the media—fully understands the ramifications of the legal context within which approvals are made.

The public also may not understand the context within which FDA makes decisions about recalls of particular foods or medical products. By helping the public better understand how it approves and recalls products, FDA can complement its rigorous premarket review and postmarket actions. To make informed decisions about products coming on the market—as well as those being removed from the market—users need to understand the concepts of risk and benefit. They also need to understand their roles (e.g., prescriber, patient, caregiver) in managing the risks of using FDA-regulated products.

Equally important to understand is the natural tension that results from communicating what we know from research about a product’s risks and benefits. In research, scientists collect evidence for a population: summary risks and benefits are therefore accurate for a population in general, but may not be so for a specific individual, who may react differently than the average individual.

Emergency-related communication is particularly challenging

Communicating during emergency events, such as food recalls, presents unique challenges. Over the course of a recall, as both FDA and the industry gather more information, advice for consumers can change significantly. That change can result in confusion. Once a recall is over, effective communication is needed to ensure that consumers can understand and be assured that it is once again safe to consume the previously recalled product. There may be significant nutritional or other consequences should consumers decide permanently to shun previously recalled products. Additionally, there may be economic consequences when recalled U.S. products are sold in foreign countries, particularly if such recalls affect the image of FDA products generally.

Challenges of Effective Risk Communication: Illustrative Examples

What is effective risk communication in relation to FDA’s mandate? These three examples illustrate some of the challenges of risk communication. For all three, the ultimate decision about whether to act on warning information is made by an individual, taking into account the information received, his or her own knowledge, values, and, sometimes, consultation with a medical professional. But each person needs to receive and understand the information necessary to help inform choices. To be able to communicate effectively, FDA needs to apply some basic principles of risk communication and conduct appropriate tests to understand how people interpret communications.

Example 1: Implanted Devices

The Facts: Many American families have a member with an implanted device helping to keep a regular heartbeat. After years of experience with the device implanted in many people, the manufacturer learns that a small device piece may fail in an extremely small number of people. The manufacturer and FDA decide that devices that have not yet been implanted should be recalled. In most cases, the risks of removing the device outweigh the risks of leaving the device in, given the benefits of the device for the patient. How does communication ensure a successful recall of the remaining devices without causing undue concern for those with the device already implanted?

The Challenge: Some worried patients may make unnecessary office visits, and even potentially harmful decisions about removing a device that is providing a significant benefit—a benefit that outweighs the risk of device failure.

Effective risk communication: Effective risk communication achieves both of the desired ends—an effective recall and an informed patient—in a way that avoids patients making potentially costly and dangerous decisions. This generally means that a complex set of risk and benefit information must be communicated in a way that consumers will attend to, understand, and be able to apply to their individual situations.

Example 2: Contaminated Foods

The Facts: As part of a healthful diet, American families are urged to eat fruits and vegetables. Yet, on occasion, a particular type of fruit or vegetable (or other nutritious food product) may be the source of foodborne illness and FDA will issue a recall or a warning to the public to avoid eating that particular product.

The Challenge: To avoid illness, FDA would like consumers to stop eating the fruit or vegetable recalled or implicated in an outbreak. However, FDA would also like consumers to return to eating the fruit or vegetable once the suspect product has been removed from the market shelves. Research shows, however, that consumers don’t always know that a recall or outbreak has ended. Findings also show that many consumers, even those who know that the suspect product is no longer available for purchase, continue to avoid the item, thus restricting their own access to a source of nutritious food.

Effective Risk Communication: This case demonstrates the need to sufficiently communicate to consumers that an outbreak or recall is over, and that it is possible once again to get the benefits of the nutritious fruit or vegetable.

Example 3: Prescription Drugs

The Facts: Prescription drugs help cure or manage health conditions for many people. For many drugs to work, it is critical that a patient take all of the prescribed doses in the prescribed fashion.

The Challenge: Many people don’t take drugs as directed. Many people don’t want to think of themselves as sick, and taking drugs makes them feel that way. Sometimes, people stop taking their drugs when they feel better, even though the condition is just temporarily hidden and could return. Some drugs interact with others, so when taking multiple products, patients must take them exactly as prescribed, which might be hours apart. This can be especially problematic for older patients. If a patient does not follow the regimen, a bad outcome may occur. For example, the illness may return because it was not completely treated in the first place. Or drugs taken in combination may interact in dangerous ways. Some patients or caregivers may give themselves or their children overdoses. There are times when people take drugs as prescribed and new safety information becomes known months to years after marketing.

Effective Risk Communication: Clear and easily understood information on prescription drug labels and instructions for use, as well as extra efforts to target specific identified problems and populations, can help ensure appropriate and safe use. For example, if particular drugs are more likely to be used by elderly people, considering carefully that group’s cognitive limitations could lead to instructions for use that are more likely to be followed.

Defining Risk Communication for the Future

In the past decades, FDA’s awareness has grown about the breadth of what constitutes risk communication. This is consistent with the general growth in acceptance of risk communication as a broader process than one-way messaging about risks from experts to non-experts.6 Risk communication that seeks to be effective needs to consider processes and procedures in addition to content. In pursuit of a shared acknowledgment of how FDA conceptualizes risk communication, a cross-FDA group of staff involved in communications agreed on the working definition of FDA risk communication described in the following section.

Risk communication is multifaceted

In the context of FDA’s responsibilities, risk communication activities fall into two broad categories: (1) interactively sharing risk and benefit information to enable people to make informed judgments about use of FDA-regulated products and (2) providing guidance to relevant industries about how they can most effectively communicate the risks and benefits of regulated products.

The first category relates to FDA’s function as an information-generator. In this capacity, FDA produces and disseminates information about regulated products to the press and various stakeholders, including consumers, healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, physician assistants, pharmacists, veterinarians, hospital and nursing home administrators, and health plan managers), caregivers, patients, public health officials, and regulated industry. Such information includes notices of product approvals, announcements and advisories about new public health related information, notices of product recalls, notices of U.S. recalled products distributed to foreign countries, and educational information about proper product use and safe food handling practices.

The second category relates to how the agency oversees what regulated industry says about its products. Manufacturer- and producer-generated product information represents most of what users hear about FDA-regulated products. This information makes up a large part of what users know about a product and is critical to ensuring that they use a product appropriately to achieve maximal benefit. By enforcing the rules and providing useful guidance to industry around product information (labels, other printed information, and in select cases, product advertising), FDA can influence user knowledge and consequent behavior.

Underlying this definition of risk communication is the recognition that even if people are getting direct FDA recommendations, it is ultimately an individual’s personal choice to, for example, purchase a prescription drug and take or give it to their pet, pick the right food choice for their health, use a medical device appropriately for a particular patient, or avoid unnecessary exposure to radiation. It is critical that individuals receive information that is adequate to ensure that they make informed choices.

Risk communication conveys the potential for bad and good outcomes

Risk communication is about conveying the possibility of both bad and good outcomes. For example, with respect to medical products, without the expectation of benefit, people are unlikely to accept even a small amount of risk. With respect to foods, there are many questions concerning the net value of particular foods or nutrients for addressing health conditions. Furthermore, in the absence of understanding that foods provide nutritional benefits, members of the public may respond to a food product recall by permanently halting their use of that food or food type. This would be an unintended bad outcome of a recall notice. Therefore, risk communication must involve describing both the risks and the benefits of regulated products, including adequate instructions to guide appropriate use.

Risk communication is a two-way street

FDA recognizes that risk communication with the public is a two-way street. Without a dialogue, FDA cannot learn the needs of its varied audiences or attempt to meet those needs successfully. This concept of two-way information sharing is implicitly embedded in FDA’s provision of guidance to regulated industries. The government is committed to the interactive development of policy. Similarly, we believe the same should be true, whenever possible, of risk communication.

FDA committed to this concept of two-way communication with its Transparency Initiative. Consistent with the principles discussed in this Strategic Plan, in Spring 2009 FDA formed the Transparency Task Force to develop recommendations for making useful and understandable information about FDA activities and decision-making more readily available to the public in a timely manner and in a user-friendly format. The Task Force will develop a report to deliver to the FDA Commissioner six months from its formation. FDA has already held one public meeting and is planning another to get input from stakeholders on how to make our regulatory decisions available in a timely and effective manner. In addition to the public meetings, FDA established a blog as another vehicle by which the public can provide input to the Transparency Task Force.7

Underlying Principles

A number of underlying principles guide FDA’s strategic planning and commitment to activities that will improve how the agency conveys the risks and the benefits of regulated products.

Risk Communication Is Science-Based

First, FDA has a long-standing commitment to being science-based and science-led, a commitment that also includes risk communication activities. FDA fully supports using scientific methods to design and assess communications that will ensure maximum effectiveness. The science of risk communication and previous work in this area demonstrate important ground rules.8 For example, it is crucial that the information in a document be both cognitively accessible9 and relevant to the target audience.

However, having general ground rules is not enough. Although there are general principles for designing communications, they are not algorithms; we must still assess whether specific messages are reaching and being understood by the various target audiences. To use an analogy, consider how FDA assesses drugs. Previous work has established the general principle that an effective drug will show a dose–response curve. The dose for the specific drug and its use in particular populations, however, must still be assessed before FDA can decide whether the drug is effective and how it should be administered. Risk communication must be viewed similarly.

Risk–Benefit Information Provides Context and Is Adapted to Audience Needs

A second guiding principle is that for people to make informed decisions, they need access to critical risk and benefit information—adapted for their specific needs—when, where, and in the form they need to best understand and apply this information. Furthermore, communication must be adapted to meet the needs of many groups who differ with respect to literacy, language, culture, race/ethnicity, disability, and other factors.

One of FDA’s essential roles is to ensure that its various audiences get the information they need to make informed choices. Audiences must also be aware of and understand the context of that information or it will have little meaning. FDA recognizes that patients and consumers make choices to take particular actions. In developing communications, FDA must consider and, when appropriate, address the possibility that people may react to facts from emerging risk information out of context, choosing actions that are not beneficial and may be harmful.

Finally, audiences have different levels of understanding about the context of the information they receive. For example, information that could be interpreted as representing a significant change in FDA’s position on a product’s overall value could be misleading or confusing to patients and other members of the public.

To enable informed decision-making that ensures the greatest possible personal benefit at the lowest possible personal risk, at minimum people require objective facts about the risks and benefits of product use. People also may need facts about the risks and benefits of not using a particular product, what is known and not known about the product—and perhaps even the limitations of that knowledge. For example, FDA relies on a voluntary and passive adverse event reporting system. The system provides data of varying quality and hence different degrees of understanding and confidence that the understanding gained is speculative or definitive. Consequently, communications must also be framed so that audiences can understand the decision-making process that led to the communication and any recommendations that come from those decisions.

FDA’s Approach to Risk Communication Is Results-Oriented

As a public health agency, FDA is committed to protecting and promoting the public health. The effectiveness of all of FDA’s risk communication activities must ultimately be measured against how successfully we achieve this goal. For example, long-term health outcomes key to FDA’s mission include ensuring that the public realizes the maximal benefits and minimal risks possible from informed healthy food choices and safe food preparation. Similarly, healthcare professionals, patients, consumers, and caregivers should make choices about medical products that maximize product benefits and minimize harm. FDA is working to reduce preventable harm by making sure that healthcare professionals and consumers have the information they need to prescribe medicines and use medical devices and medicines appropriately, in accordance with the science-based advice provided in product labeling.10 Communications are playing a key role in this effort.

FDA must find ways to measure the success of its communications on these long-term public health outcomes. However, we must keep in mind that individual attitudes and behaviors are influenced by a variety of factors, including communications by other government agencies; advertising by product manufacturers and distributors and other organizations that have their own specific agendas; individual values and needs; and factors in the “immediate situation” 11 (e.g., social norms, financial incentives and disincentives). In other words, placed in the risk communication context, FDA may have done all that it can by ensuring the public receives, understands, and can apply the information needed to make informed decisions with respect to a regulated product, even if people decide to act differently from what FDA or their physicians recommend.

Despite these possible hurdles, FDA must continue to work toward improving long-term public health outcomes as well as intermediate and near-term outcomes, which may be more under FDA’s control and which are critical if FDA is to have the best chance of improving public health. Examples of intermediate outcomes include the following:

Improved understanding of the risks and benefits of regulated products by the multiple audiences with whom FDA communicates, including relevant international audiences;

Increased public awareness of crisis events and the increased likelihood that affected individuals or groups will take recommended actions;

Increased public satisfaction with FDA as an expert and credible source of information about regulated products; and

Increased confidence that target audiences are getting useful, timely information as it becomes available, to help them make informed choices.

Immediate or near-term outcomes should also occur as a direct result of improved FDA communication activities. These outcomes will benefit both FDA and the public. Examples of immediate outcomes include the following:

Increased use of plain language and documents written so that they are understood by audiences with limited proficiency in English or limited health literacy;

Increased quality and timeliness of FDA messages;

Improved capacity for handling public inquiries;

Increased feedback on the effectiveness of FDA communications by healthcare professionals and members of the public;

Increased number of highly credible Web sites linking to important FDA communications;

Increased press satisfaction with FDA media relationships;

Improved industry adherence to promotion-related regulations; and

Improved industry understanding of when FDA will take regulatory action.

FDA must find ways to ensure that all of these outcomes are measured and tracked. Measuring outcomes will provide the feedback needed to know if and when FDA should revise its communications strategies and activities.

Strategic Goals

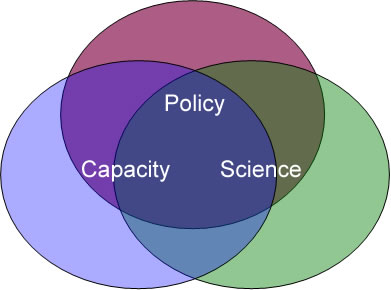

The graphic below shows the three areas of strategic focus that form the foundation for FDA’s Risk Communication Strategic Plan. Depicting these three focus areas as intersecting circles illustrates that in practice they often overlap. Both individually and together, they support improved risk communication. Some of the strategies discussed later in this document contribute to two or even all three Strategic Goals.

The three overarching Strategic Goals that will help the agency develop a 21st century communications model are as follows:

Strengthen the science that supports effective risk communication

Expand FDA capacity to generate, disseminate, and oversee effective risk communication

Optimize FDA policies on communicating product risks and benefits

Following discussion of each strategy, we present a list of the actions that FDA believes must be taken over the next five years to reach these goals. As already mentioned, some of the actions address more than one strategy within the particular goal and may overlap across goal areas. A concise table listing the goals, strategies, and associated actions is provided in the Appendix.

FDA has identified 14 specific actions the agency feels are significant and can be accomplished within the next 12 months. These actions are indicated in bold font in the action boxes that follow. They are also highlighted in the Appendix. We plan to work with relevant stakeholders in completing these tasks. FDA will evaluate the resource needs to implement the specifics of this plan through the annual budget process.

Strengthen the Science That Supports Effective Risk Communication

FDA depends on the best and latest science to make regulatory decisions about product safety and effectiveness (i.e., risks and benefits for consumers or patients). We acknowledge that, to the extent possible, this same science-based approach should guide communications activities. The agency recognizes that time and resources largely determine the extent to which we can apply lessons of science in the communications arena. For example, we cannot conduct external formative and evaluative consumer research of every individual announcement before releasing it, but we can incorporate more testing than we presently conduct. Although FDA has made progress in providing the scientific support for some communications and communications-related policy decisions, more needs to be done. Toward that end, FDA has identified three basic strategies that should ensure more consistent application of the scientific perspective to communication activities.

Science Strategy 1: Identify gaps in key areas of risk communication knowledge and implementation and work toward filling those gaps

It is apparent that many gaps remain in our knowledge of the communication needs of our various audiences. A few sample questions include the following:

How much and what kind of risk and benefit information do healthcare professionals and patients need to make informed decisions on appropriate prescribing or use of a particular medical product (respectively)?

How do healthcare professionals, consumers, and patients integrate new information into their existing belief models about the risks and benefits of medical products?

What is the effect of including quantitative information about the risks and benefits of prescription drugs or medical devices in information to patients and consumers?

How much benefit information needs to accompany risk information to create a balanced perception of a medical product?

What major motivators persuade an individual to use nutrition facts labels for making informed dietary decisions?

What do patients want to know about the risks and benefits of not using a particular medical product?

What key groups are most likely to misunderstand risk and benefit communications?

How can the agency best communicate with foreign healthcare professionals, consumers and patients that may also be affected?

Furthermore, to provide audiences with the context they need to understand FDA actions, especially the degree to which FDA can take specific actions to ensure public safety, we need to better understand the public’s knowledge of the scope of FDA’s authority.

With this in mind, a key action item under this strategy to strengthen FDA’s risk communication science is to create a prioritized risk communication research agenda. Such an agenda would have a dual purpose—to guide FDA’s own decisions about the risk communication research it should conduct and to encourage and facilitate academic and private-sector research that explores risk communication issues of interest to FDA.

Actions to Strengthen Science Strategy 1

- Produce research agenda for public dissemination and provide technical assistance and other support to facilitate research

- Develop and conduct research to determine the most effective format and content for communicating information about prescription drugs to patients receiving new prescriptions

- Develop and conduct research to determine the most effective format and content for communicating information to clients about new prescription drugs for companion animals

- Develop and conduct research to determine the most effective format and content for communicating information about medical devices to users and prescribers

- Conduct research to provide feedback about the effectiveness of FDA communication activities

- Develop an expert model to characterize tobacco-use related consumer decision-making and better understand the likely impact of FDA oversight of tobacco products

Science Strategy 2: Evaluate the effectiveness of FDA’s risk communication and related activities and monitor those of other stakeholders

It is essential to understand the basic needs of our diverse audiences. How do we best communicate the facts we have so that all members of the public will understand and use them? In addition, effective health and risk communication involves conducting formative and evaluative research. Formative testing includes initial research into audience needs and decision strategies around particular issues, along with message pretesting. Such steps are important to ensure that audience feedback is incorporated so as to maximize the efficacy of the message design process. In this way, initial areas of confusion and misinterpretation can highlight aspects of a message that require further work. Conducting evaluative research following the use of a message or tool is also necessary—especially if using a new approach—to decide if the approach is effective in achieving its objectives and to clarify whether revision is needed.

For example, FDA’s Office of Women’s Health (OWH) regularly uses focus groups to test the educational materials it issues and provides those materials in multiple languages.12 OWH works with its dissemination partners to assess the materials’ effectiveness on individual beliefs and behaviors. Similarly, FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition has evaluated educational campaigns about safe food handling practices to ensure that communication objectives are met. Surveys of consumer food safety knowledge, attitudes, and behavior are regularly conducted to help determine the effectiveness of food safety campaigns and the direction of future education programs. But evaluation is not a consistent practice across the agency. FDA is committed to working toward more consistency in assessing and evaluating its own communications.

FDA is also striving to ensure that it and regulated industries, as appropriate, evaluate the communications and communication-related activities conducted in response to regulatory mandates. For example, Section 901 of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 requires evaluations be conducted to determine whether to modify the elements of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS)13 for a subset of prescription drugs with serious risks.

As a further example of ongoing efforts, in renewed dialogue between FDA’s Office of Special Health Issues (OSHI), including its MedWatch staff, and multiple healthcare professional organizations, FDA asked for feedback on what their members knew about the MedWatch program’s products. The agency also asked how to improve written communications so it could help these organizations inform their membership about emerging risks associated with medicines and medical devices. The information gleaned from this dialogue is providing feedback about success to date and is guiding FDA in improving future communications.

Actions to Strengthen Science Strategy 2

- Design the first of a series of surveys of the general public to assess their understanding of, and satisfaction with, FDA communications about medical products, to provide a template for regularly surveying significant FDA target audiences

- Establish FDA Web portal for receiving informal comments/feedback from different stakeholders (especially healthcare professionals) about FDA’s risk communication efforts

- Issue guidance on sponsor evaluation of Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) for drugs

- Monitor media and Web coverage of risk communication messages and survey consumer understanding and reported behaviors in response to risk communication during a food outbreak/recall

- Assess utility/effectiveness of social media tools (Web 2.0) for reaching target audiences, including how the social media is covering FDA’s messaging during a recall

Science Strategy 3: Translate and integrate knowledge gained through research/evaluation into practice

Knowledge is gained through basic research, formative testing, and message or program evaluation. However, that knowledge has no value to any organization unless it is packaged in a form that can be circulated and used by those who need it. Having formal processes in place to disseminate research results and lessons learned within the organization will prevent the same mistakes from recurring. FDA is committed to ensuring that knowledge acquired through research and evaluation will be translated so as to be useful to communication designers, effectively disseminated, and incorporated into agency communication practices.

FDA has recently completed and is analyzing data from a survey of physicians about their use and perceptions of emerging risk information on medical products, including:

- the impact of news about emerging risks on their patients and practices,

- when and how they would like to receive such information,

- what sources they find most trustworthy,

- the degree to which they use electronic sources, and

- the factors that influence whether they report medical product problems and adverse effects.

For this information to be useful, it must be analyzed with an eye to the needs of its audiences—in this case, FDA staff. The information must be marketed internally and presented in a way that will best meet the requirements of relevant staffers to help produce communication materials that reflect this new data on stakeholders’ needs.

Actions to Strengthen Science Strategy 3

- Review literature and apply findings on how to translate research findings to be useful for FDA risk communication developers

- Create and maintain a useful, easily accessible internal database of FDA and other relevant risk communication research

- Increase intra-FDA exchange about research, application, and best practices among Centers

- Train FDA staff on health literacy and basic risk communication principles, considerations, and applications

- Translate health literacy research to be easily implementable in practice and communicate about health literacy best practices across agency components

- Regularly measure public documents’ plain language and appropriate reading level for target audience

Expand FDA Capacity to Generate, Disseminate, and Oversee Effective Risk Communication

Along with obtaining the scientific knowledge needed to prepare effective risk communications and evaluate impact, FDA must be able to apply that knowledge. Doing this effectively and efficiently requires that the operational capacity of FDA’s communications be adequate and that the processes associated with developing and coordinating risk communications be optimal. FDA has identified seven strategies it believes will expand its capacity both to generate effective risk communication and to oversee effectively the risk communication-related activities of regulated industries.

Capacity Strategy 1: Streamline and more effectively coordinate the development of communication messages and activities

Risk communication-related activities take place at many levels within FDA, including within the product-focused centers, the Office of Regulatory Affairs, and the Office of the Commissioner. To ensure that FDA speaks with one voice, efficient internal and external coordination are required. In addition to coordinating internally and with the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), FDA often shares responsibility for dealing with certain products or addressing food-related contaminations or outbreaks with other Federal government agencies, including, among others, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), as well as state and local agencies, foreign governments, and foreign regulatory counterparts. In these cases, seamless coordination among the agencies increases the timeliness and consistency of communications on identical issues.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 1

- Improve intra-agency coordination of message development with sister agencies on issues that affect other HHS Operating Divisions

- Improve coordination with states and localities on multi-state food outbreak and recall communications

- Develop templates for FDA press releases about regularly occurring events (e.g., approvals, recalls, public health advisories/notifications)

- Develop mechanism to track time to clearance and dissemination of press releases

- Assess and improve procedures for developing and disseminating cross-FDA messages and communication products

- Launch FDA-wide wiki and other appropriate Web-based tools to share information and work collaboratively more effectively

- Increase OPA and other media relations staff, especially with translation capability

Capacity Strategy 2: Plan for crisis communications

Many crisis communication situations—especially disease outbreaks related to food contamination—are true emergencies in which FDA and its partners (see Capacity Strategy 1) must develop and disseminate communications unexpectedly, swiftly, and often on a continual basis. In such cases, FDA is unlikely to have thoughtfully developed and tested messages available for a specific emergency. But the agency can apply lessons from similar past experiences as well as its knowledge of the products that are most vulnerable to contamination—accidental or deliberate. FDA can use these lessons learned to develop general procedures, tentative communication dissemination plans, and prototype messages for various audiences that can be adapted to specific circumstances.

For example, FDA is analyzing data from interviews with consumers focused on their awareness of the possibility that food could be a vehicle for a terrorism event. The agency will use this information to develop strategies to communicate more effectively with consumers should such an event occur. The agency is also creating an FDA call center that will improve how the agency handles phone calls about regulated products that are received outside of normal business hours. In a related move, FDA is increasing its surge capacity for managing a larger-than-normal volume of emergency-related calls during and outside of normal business hours.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 2

- Establish decision matrices or question sets for:

- what constitutes emergencies and/or crises for FDA

- determining when an emergency has occurred and when it is over

- when FDA will communicate about changing product risk information

- Establish a significant new data collection mechanism to measure consumer reaction to food recalls and outbreaks on a just-in-time basis to adjust messages during the emergency for the greatest effectiveness

- Update FDA and CFSAN Emergency Response Plans to streamline roles and responsibilities for communications during an outbreak/recall

- Establish micro-blogging mechanism (e.g., Twitter) to send short urgent messages on public health notices, recalls, etc. to keep public informed of latest developments

- Regularly and frequently communicate with media during crises

- Develop a “library” of multi-media communications on safe food practices for general education purposes, and for use in conjunction with crisis communications concerning food contamination episodes (e.g., safe handling of produce, food safety during a power outage)

- Develop educational communications on the inherent limitations of the data FDA uses to make decisions about regulated products and what this means for public beliefs and prevention behaviors

- Develop and implement educational programs and activities to increase the understanding of the public, healthcare professionals, and the press about medical product regulation

Capacity Strategy 3: Streamline processes for conducting communication research and testing, including evaluation

FDA is committed to:

- conducting and encouraging others to conduct the research and testing needed to develop and disseminate communications, according to evidence of how they are likely to be encountered, attended to, understood, and acted upon by target audiences; and

- evaluating the degree to which a communication process was successful in achieving its objectives.

In fact, past FDA research has informed various communication-related initiatives, including development of:

- the Nutrition Facts label for foods;

- the Drug Facts label for nonprescription drugs; and

- format revisions to prescription drug prescribing information.

FDA is conducting research on both the detailed information (often referred to as the “brief summary”) required for inclusion in prescription drug advertising directed to consumers and how consumers interpret various statements on the front-panel display of food labels. However, this research often takes years to develop and carry out. FDA is committed to streamlining the required processes for moving research projects from conception to implementation so as to make these processes as efficient as possible.

Producing effective communications requires that initial drafts be tested, preferably with target audience members. This enables drafters to determine whether the communication is meeting its objectives and whether there are likely to be unintended negative or unexpected effects. However, the lengthy process needed to gain approval for conducting research and testing can make it difficult to test communications with more than nine14 members of the public in the time needed for rapid communication, especially about emerging risks of regulated products.

Piloting message testing with government employees as public surrogates

Streamlining processes as much as possible is one part of this solution. Another part relates to FDA’s policies (see also Policy Strategy 3). While FDA moves toward these improvements, it is also piloting the feasibility of having government employees serve as public surrogates to informally test messages and communication formats before issuing messages, especially when it is critical to communicate quickly with the public. There are many employees who could be reasonable surrogates for different members of the public on a given topic, because their work lies in areas significantly different from the topic in question. Also, this allows testing messages that could be difficult to test with the public because the information is confidential.

Employees would be selected, to the extent possible, to represent socio-demographic diversity, respecting literacy, language, culture, and other key factors. FDA realizes that this is not a scientifically ideal solution because employees are not likely to be completely representative of the agency’s target audiences. However, this approach is much more readily implementable than an external study and would enable testing prior to making a message public.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 3

- Establish an internal network to test messages informally with FDA employees

- Improve procedures and mechanisms that enable FDA to conduct timely testing of public risk/benefit communications

- Explore new collaborative relationships that can provide timely data on effectiveness of high-priority communications

Capacity Strategy 4: Clarify roles and responsibilities of staff involved in drafting, reviewing, testing, and clearing messages

Within FDA, a need exists for greater clarity about who in the communications review chain is responsible for determining that an information piece has been sufficiently refined for a particular target audience. FDA’s messages about regulated products are scrupulously reviewed by staff members with different types of expertise. Depending on the product and issue, reviewers may include physicians, pharmacists, biologists, chemists, pharmacologists, nutritionists, engineers, communications professionals, attorneys, compliance officers, and policy analysts.

Although the targeted audience is often non-medically trained patients or caregivers, it is uncommon for anyone from that target audience to be included in the review chain. Consequently, messages initially designed to communicate a simple point can grow excessively lengthy and complex. Expert staffers understandably want to ensure that the message is scientifically and legally precise. However, stakeholders have frequently told FDA that the resulting messages are too complicated and not easily understood by non-specialists.

FDA also believes that it can improve the internal review process by raising reviewers’ awareness about factors that must be explicitly balanced for the best communications results. For example, reviewers could be further educated to consider the needs of certain vulnerable populations, including those with limited English proficiency, limited health literacy, or limited ability to understand and use numbers or statistics (numeracy).

Reviewers can also be educated to weigh the benefits of including highly detailed information that provides greater precision against the increased likelihood of information overload. A shorter, more focused message may not address an issue’s every nuance, but it ensures that a less literate audience will be able to understand critical messages and recommendations. Tiering the information—providing a shorter and simpler message first, followed by additional detailed information for those who want it—may help achieve a balance in these competing, but worthy, objectives.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 4

- Develop FDA guidelines specifying roles and responsibilities of different FDA experts in communications development

- Educate scientific and legal staff/reviewers on audience needs, trade-offs between information precision/completeness, and information overload

Capacity Strategy 5: Increase staff with decision and behavioral science expertise and involve them in communication design and message development

As a result of the issues discussed in previous sections, producing effective FDA risk communications and ensuring that regulated industries produce effective risk communications have become increasingly important FDA functions. Fischhoff15 asserts that effective risk communication requires the contribution of four types of specialists:

- domain specialists,

- risk and decision analysis specialists,

- behavioral science specialists, and

- systems specialists.

Applying this framework to FDA staffing, it is clear that the agency has many domain specialists—individuals with expertise in medical and physical sciences who understand the risks and benefits data that need to be communicated to product users. But FDA is not well staffed with the risk and decision analysts needed to identify the information that is necessary to user choices. Nor does it have the number of behavioral scientists it needs to design and evaluate messages. Finally, while communications systems specialists are somewhat better represented within FDA, more are needed to create and use communication channels more effectively.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 5

- Hire individuals to increase appropriate expertise

- Train existing FDA staff to understand need for formative and evaluative research, how to apply known decision/behavioral science findings

Capacity Strategy 6: Improve the effectiveness of FDA’s Web site and Web tools as primary mechanisms for communicating with different stakeholders

FDA’s Internet Web site is a primary vehicle for communicating with the public—both directly and through the press. This is especially so when FDA is conveying information about new and potentially uncertain or emerging risk information, product recalls and warnings with significant public health consequences. FDA’s Web site provides a wealth of information about:

- how products are reviewed;

- how product quality is monitored;

- The myriad regulatory and policy actions the agency takes;

- how external advice has been given to FDA; and

- how FDA takes advice into account when it acts.

However, the volume of information provided has a downside. In December 2005, FDA held a public hearing about the effectiveness of the agency’s risk communication strategies for human drugs. Stakeholders told FDA that its drug-related Web information is difficult to navigate and needs to be redesigned to make it “more accessible and user-friendly as well as to address specific health concerns of patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.”16

FDA recently launched a Web Content Management System designed to improve the timeliness, ease of navigation, usefulness, and usability of its Web materials. As part of this modernization effort, FDA is also removing outdated, extraneous, and unused materials. The agency has also begun making changes to its Web site to improve its information architecture.

In addition, FDA recognizes the need to explore the variety of electronic tools that fall under the broad scope of the Internet. The agency already uses e-mail distribution lists, RSS feeds, podcasts, widgets, and other tools when appropriate for a particular communication purpose. However, the ever-expanding supply of new tools highlights the need for constant vigilance in assessing the potential value of these tools for improved communication.

Forming Web partnerships to broaden FDA information distribution

The agency has begun forming partnerships with organizations to maximize the distribution of FDA’s information. It recognizes the current limitations of its Web site and that many stakeholders access other sites more frequently than FDA’s. Thus, in early December 2008, FDA announced a formal partnership arrangement with WebMD, which will make consumer health information associated with FDA-regulated products more accessible by having an FDA-focused Web page on WebMD’s site.17 The agency is pursuing other partnership arrangements, including with the CDC, to examine the value of social media and networking tools to communicate time-sensitive product information expeditiously.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 6

- Regularly report/disseminate existing Web use statistics to FDA message developers, broken down to extent possible by targeted audiences

- Increase number of pages/sites that provide a targeted feedback mechanism

- Develop video streaming on consumer safe food handling practices to prevent illness and place on Web and external media distribution sites

- Regularly monitor non-FDA Web sites that misleadingly report FDA information and develop talking points, where appropriate, to address miscommunications

- Assess value of establishing an FDA Web page to provide information to the public on false Internet rumors about FDA actions, or work with existing Web sites to achieve the same goal

- Increase use of Center- and project-specific blogs and other social media tools for communication with the public

- Establish specific FDA Web site to serve as central portal for public to obtain pictures of all approved medical products with known counterfeits

- Post pictures of FDA-regulated products affected by class I or high-priority class II recalls as part of recall notices/information

- Explore creating a virtual world associated with FDA’s Web site to show FDA inspection activities at facilities and at the border

- Examine feasibility and cost of Web-based software needed to establish social networking tools (e.g., virtual forums, lecture series, training) to enable FDA professionals to connect with internal and external colleagues to maintain current understanding of the most up-to-date research, policies, practices, and techniques in their fields

- Explore and examine feasibility of using different electronic options (Web tools, electronic entertainment systems) to communicate the risks of tobacco use

Capacity Strategy 7: Improve two-way communication and dissemination through enhanced partnering with government and nongovernment organizations

At the December 2005 public hearing on the effectiveness of FDA’s risk communication strategies for human drugs, some participants commented that the agency should “concentrate on its traditional role of providing benefit–risk information to healthcare practitioners that would improve patient dialogue.” Participants also advised FDA to target specific specialties and work closely with those groups to “optimize education in risk communication.”18

Improving relationships with healthcare professionals

FDA acknowledges that ensuring continual dialogue with healthcare professionals is crucial. In fact, within the past few years, the Office of Special Health Issues (OSHI) re-established FDA’s efforts to develop and maintain productive relationships with medical, nursing, and pharmacy professional organizations and is committed to continuing this approach. OSHI and the MedWatch staff are working with several organizations to explore mechanisms for targeting MedWatch safety alerts to a subscriber subset who wish to receive selected notices. Through OSHI, FDA is working with the American Medical Association and medical specialty groups to develop networks for two-way communication, including a pilot project for targeted messaging with the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Improving relationships with other government stakeholders

FDA also recognizes that it needs to establish and continue to improve working relationships with other government agency stakeholders including CDC, USDA, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Veteran’s Administration (VA), individual states and localities, international organizations like the World Health Organization, and foreign regulatory counterparts.

Sharing early information with other stakeholders should make working relationships more effective and place greater value on collaboration. FDA has established memoranda of understanding with DoD and VA to improve communication with these organizations, which have information about and responsibility for large numbers of patients. The Risk Communication Staff in FDA’s Planning Office have also set up regular teleconferences with Health Canada regulatory and communications officials to improve coordination of strategic risk communication.

FDA has created an FDA Federal-State Partnership for Food Protection Coordinating Committee, comprising Federal partners (FDA, CDC, USDA, and DHS) and a wide range of state, territorial, tribal, and local representatives. This is a strategic and technical committee that advises FDA on necessary infrastructure and food safety implementation strategies essential to building a national food safety system. Partnership for Food Protection work groups are currently focused on improving interactive information technology (IT), training, response, and risk-based work planning. A work group was also formed to facilitate the development of a Pet Event Tracking Network (PetNet). All these activities require regulatory and public health partners to share information and coordinate on risk communications.

FDA and the foods industry, through a non-profit consortium, have collaborated successfully on joint educational efforts. This collaboration represents another type of partnership that FDA aims to advance. Along with USDA and CDC, FDA is a member of the Partnership for Food Safety Education, which unites industry associations, consumer groups, and professional societies in food science, nutrition and health. This not-for-profit organization is the steward of the Fight Bac campaign that is designed to prevent foodborne illness through public education about safe food handling practices.

Actions to Expand Capacity Strategy 7

- Establish procedures for using select healthcare professional associations to evaluate comprehensibility of communications targeted at their stakeholders

- Partner with clinical facilities in MedSun network to assess impact of FDA recommendations for device safety

- Partner with consumer and patient organizations to obtain feedback about comprehensibility and usefulness of FDA communications

- Identify and partner with consumer and patient organizations to increase availability of FDA communications in a variety of languages and for literacy-challenged audiences

- Solicit feedback from reporters who cover FDA on ways the agency can be more responsive to requests for information

- Expand efforts to partner with Web sites that consumers and healthcare professionals regularly visit to increase external links to FDA information about regulated products

- Regularly assess whether advisory committee meetings effectively facilitate two-way communication

Optimize FDA Policies on Communicating Risks and Benefits

The third strategic goal focuses on FDA’s policies on risk communication. Applying the results of the science goal strategies and implementing some of the capacity strategies requires streamlining internally and externally focused FDA policies. Three strategies under the policy goal target internal policies governing FDA-generated risk communications. The fourth strategy targets policies associated with risk communications that FDA oversees.

Actions to Optimize All Goals and Strategies

- Identify outcomes and develop measures for assessing progress toward goals and strategies

- Develop detailed action plans at agency and Center levels for implementing the strategies and achieving the proposed action steps, including timelines, responsibilities, and resource needs

Policy Strategy 1: Develop principles to guide consistent and easily understood FDA communications

Risk communications would be better understood and applied if internal policies were established specifying the kind of information that should be consistently included. For example, FDA’s Risk Communication Advisory Committee has repeatedly recommended that FDA’s risk communications include both product benefit and risk information, presented to the extent possible in quantitative formats.

Additionally, some Committee members have noted the need to ensure that the public understands fully the context of approvals and recalls. For example, risk communications about approved products may at times need to state clearly that efficacy and risk information was established only for a product’s intended use(s) and might not apply if someone uses it in another way. FDA also may need to address how to improve public understanding of the limits of FDA’s authority, at least to the extent it is relevant to informed decision-making about regulated products (see also the discussion in Science Strategy 1).

Based on the information from literature, testing, and basic research, other evidence-based principles for communication documents could address the following examples.

- When to include the risks and benefits of not using particular products associated with emerging risks.

- How to ensure that information is accessible to lower literacy audiences.

- How tiering or layering messages can improve communication of critical information.

- How to ensure the clarity of product-use recommendations.

- How people can get additional risk communication/information.

Actions to Optimize Policy Strategy 1

- Develop a handbook of evidence-based guidelines for effective risk communication (literature review consolidation)

- Develop research-based strategic plan for branding and promoting the next generation of the Partnership for Food Safety Education’s education program, BE FOOD SAFE

Policy Strategy 2: Identify consistent criteria for when and how to communicate emerging risk information

Although FDA has moved toward communicating earlier and more transparently about emerging risks of regulated products, particularly medical products, it does not have a comprehensive, science-based set of principles about when and how to communicate this information.19 Therefore, the criteria that FDA uses to determine when to communicate about regulated products are likely to be unclear to the public. Additionally, FDA uses different types of communications to address emerging risks for different types of regulated products. Issuing multiple documents with similar purposes can be confusing for stakeholders. To avoid this, FDA must clarify, both internally and externally, when and how it will communicate about emerging risks of FDA-regulated products and how to standardize communication formats.

Actions to Optimize Policy Strategy 2

- Harmonize across FDA on appropriate criteria, titles, content, and format for public notifications of emerging risks of medical products (drugs, biologics, and devices)

- Harmonize multi-state food recall public announcements in coordination with USDA, CDC, and affected states and localities

- Harmonize international announcements in coordination with international organizations and foreign regulatory counterparts

Policy Strategy 3: Re-evaluate and optimize policies for engaging with partners to facilitate effective communication about regulated products

It is generally accepted that critical communications should be tested prior to use with the intended target audience. However, as discussed earlier, this process is often time-consuming and therefore may not be feasible in crisis situations. As Capacity Strategy 7 notes, FDA is committed to partnering with both government and nongovernment entities to improve the value and reach of its risk communications. In addition to creating a more effective interactive risk communication environment, sharing messages before issuance with organizations representing critical stakeholders (especially when the target audience is healthcare professionals) could provide some timely feedback. However, FDA’s policies on confidentiality, ethics, and other considerations require that acceptable parameters be established for such interactions.

Actions to Optimize Policy Strategy 3

- Evaluate the statutory and regulatory framework around FDA’s sharing of confidential information to facilitate earlier sharing and feedback with outside healthcare professional experts and organizations about upcoming medical product regulatory actions (e.g., warnings and recalls)

- Evaluate the statutory and regulatory framework around FDA’s sharing of confidential information to facilitate earlier sharing and feedback with state and local regulatory agencies about upcoming Federal food regulatory actions (e.g., warnings and recalls)

- Expand two-way communication with healthcare professionals about emerging medical product risk information, determine need for any additional policies and processes, and identify and approach organizations with highest potential for two-way communication

Policy Strategy 4: Assess and improve FDA communication policies in areas of high public health impact

FDA recognizes the need to consider how to optimize policies on its oversight of the communications of regulated industries. This is especially critical when industry communications deal with issues that have a major public health impact. Some of the areas that FDA is currently examining are listed below.

- Modernize effective communication in a recall. FDA issues some communications on recalls. However, product manufacturers have the primary responsibility for most recall activities, notices, and for following up with wholesalers or retailers to decide whether recall activities are addressing the particular safety issue satisfactorily. FDA is examining the impact of a recent food recall and will investigate the degree to which, if at all, new social media tools that FDA and CDC used contributed to the recall’s outcome.

- Ensure that patients get useful written information about the prescription drugs they use. On the basis of a congressionally mandated study, FDA recently determined that private-sector efforts have not succeeded in meeting congressionally mandated goals to ensure that patients filling new prescriptions get useful written information on the drugs they are given.20 The failure of these efforts allows FDA to examine the patient information program anew and potentially take regulatory action to ensure that patients get this information.

One issue may be the potentially bewildering array of written information patients receive—in multiple formats and inconsistently distributed (e.g., private sector-produced information; manufacturer-drafted, FDA-approved information, such as Medication Guides and Patient Package Inserts). Various stakeholders have noted that this excess of information and inconsistent content and formats could confuse patients and lead to error. Consequently, FDA is revisiting the current approach to the content and format of written prescription drug information provided to patients. We are evaluating how best to ensure that patients getting prescription drugs (including biologics) receive the information they need, in an optimal form and format, to use products with maximal benefit and minimal risk.

- Ensure that healthcare professionals get useful information about FDA-regulated products when and in the form they need it. Historically, FDA has focused on communicating with healthcare professionals about medical products. As well as having primary responsibility for using significant medical devices and animal drugs, these professionals have the most influence on the decisions that patients make about product use, especially drug and certain device use, and the decisions that consumers make about human and animal nonprescription drug use. As Capacity Strategy 7 describes, FDA has recently devoted additional resources to re-establishing, expanding, and maintaining relationships with medical, nursing, and pharmacy professional groups. Part of that effort has involved looking at how FDA can better provide opportunities for more effective two-way communication with these professionals. The agency is also seeking opportunities to work with them to make available information that professionals need at the time of clinical decision-making.

- Modernize the regulation of prescription drug promotion. FDA regulates both advertisements and labeling (including approved prescribing information and promotional materials like mailed literature, brochures, scientific study reprints, videos, and press releases) for prescription drugs and biologics. The current regulations were developed when such promotional materials were only directed to healthcare professionals; they may create confusion when applied to consumer-directed advertising. For example, regulations require that FDA enforce regulatory distinctions in information disclosure between the two categories of promotional materials (advertisements versus labeling), even though such distinctions are not meaningful to a targeted consumer audience.

Other regulations require that FDA enforce identical information disclosure requirements within each promotional material category (ads and labeling), regardless of whether the target audience is healthcare professionals or consumers. The result is that consumer-directed advertisements generally include highly technical information that can be difficult to sort through.

In recent years, FDA researched and solicited public comment on consumer-directed prescription drug advertisements. FDA issued guidance (some draft and some final) on how advertisements directed to consumers can provide information in language that is more easily understood by this audience and still meet regulatory requirements. In light of direction from the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, research data, and public comment, FDA is proactively developing additional guidance and devising regulations that will further address these communication issues to better meet the needs of consumers and healthcare professionals and provide greater clarity for industry.

Actions to Optimize Policy Strategy 4

- Establish a one-document solution to ensuring patients get useful written information about the prescription drugs they take, based on target audience research and feedback

- Evaluate FDA’s framework for regulating prescription drug promotional activities (advertisements, promotional labeling, sponsor interactions with healthcare professionals) and determine any need for revised or additional legislation or regulation

- Finalize guidance on presentation of risk information in medical product promotional materials

- Determine need for policies and procedures in using social media (Web 2.0) to improve two-way communication between FDA and the public on issues concerning regulated products

Conclusion

Risk communication is a critical component of FDA's mission to protect and promote the public health. FDA is launching an ambitious communications strategy that will take time and substantial collaboration with domestic and international stakeholders to implement. To succeed, the agency must address the needs of its audiences more effectively when planning and implementing risk communications on FDA-regulated products. Such an approach will also be needed when overseeing communications from regulated industry. FDA has identified areas in need of improvement. As part of its Strategic Plan for Risk Communication, FDA has begun:

- enhancing the science behind FDA risk communication;

- expanding its capacity to generate, disseminate, and oversee risk communication about regulated products; and

- optimizing its policies on communicating product risks and benefits.

Toward this end, FDA has also identified and committed to achieving within the next 12 months 14 selected actions to increase the effectiveness of the risk communication that FDA generates, disseminates, and oversees.

FDA is confident that the strategy outlined in this report will help ensure that FDA-regulated products are used appropriately. To improve public health and safety, FDA must ensure that healthcare professionals, patients, and consumers have the information they need about FDA-regulated products, in the form they need it, when they need it.

Appendix: Goals, Strategies and Associated Actions

The following table summarizes the goals, strategies, and actions in FDA’s Strategic Plan for Risk Communication. It also highlights (** and Bold font) the actions that FDA intends to complete within the next 12 months.