Public Outreach Remains Powerful Agency Tool

It was 1933. Americans were in grave danger, falling victim to an array of alluring tonics, powders, creams, and contraptions advertised on the pages of daily newspapers and women’s magazines, over the radio, and for sale at local five-and-dimes. These concoctions promised to treat everything from pallid complexion, freckles, and gray hair to diphtheria, influenza, sexually transmitted disease, diabetes, and cancer. Yet, many of those so-called cures, whose labels bore such words as “effective,” “splendid,” and “cure positively and without fail,” caused serious illness, injury—even death.

The FDA, known then as the Bureau of Chemistry, was deeply concerned. It was acutely aware of the harms posed by dangerous drugstore concoctions and cosmetics, as it received reports, including letters handwritten by Americans themselves, of immune disorders, paralysis, neurological and cognitive damage—and as one 10-year-old girl reported, her mother’s permanent blindness—all as a result of using what appeared to be simple, over-the-counter products.

Appealing to the government, on behalf of her mother and others like her, the young girl wrote: “I don’t want anything to happen to other ladies like has happened to my mother.” The woman had done little more than apply the popular eyelash and eyebrow enhancer Lash Lure, packaged in an attractive, art deco-styled box and for sale at many beauty salons in the 1930s. Despite the 10-year-old’s plea, several other Lash Lure users would suffer vision damage or, worse, blindness—until the government had the means to protect them.

Limited Authority

The food and drug safety law at the time—the 1906 Pure Foods and Drugs Act—provided the Bureau of Chemistry (eventual FDA) with oversight of many foods and drugs. But with regards to the safety and labelling of some medical products, and all medical devices and cosmetics, it was powerless. Even in instances where the law provided a path for pursuing negligent manufacturers, the burden to prove deliberate and willful violations rested fully on the agency, and many loopholes for firms to dodge responsibility existed.

Still, the nascent FDA was determined to impose some form of public health protection. And if it couldn’t achieve that through legal authorities, then, it decided, it would go directly to the people. As an agency spokesperson wrote in a 1933 press release about its responsibility to consumers, including its commitment to sharing information that could prevent harm and save lives, “we would be seriously remiss if we did not inform the public of every means possible in our power.” The FDA would proceed to do just that, leveraging all platforms it could.

“We would be seriously remiss if we did not inform the public of every means possible in our power.”

Stunning Evidence, Exhaustive Outreach

Appearing at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, the FDA’s “Chamber of Horrors” exhibit (as one reporter dubbed it) consisted of a series of foldable panels featuring tacked-on pictures and posters and looked, by today’s standards, more like a middle-school student’s science project. But its message was irrefutable. Through the use of visual, visceral tactics, agency outreach staff were able to effectively stop fair goers in their tracks.

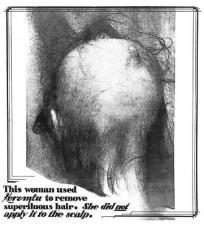

On grim display were death certificates of diabetics who had died at the hands of so-called diabetes “cures.” Under a panel entitled, “Cosmetics Are Not Subject to the Present Law—Some Are Dangerous,” attendees were met with more startling images: one of a woman’s almost-bald head; another, of a woman whose eyelids had been pulled back dramatically revealing obvious damage to her eyes. Adjacent to both were images of the pleasant-seeming cosmetics responsible for the victims’ hair loss and blindness. (The hair-removal cream Koremlu, even when used sparingly, often caused extensive hair loss or worse, and was later found to contain thallium acetate, a common ingredient in rat poison.)

According to Time magazine, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt—who would lend her powerful lobby of women’s organizations and female White House reporters to the FDA’s cause of protecting public health—was so moved by the exhibit’s images that she remarked, “I cannot bear to look at them.”

Power of the Purse

Public service announcements on the radio programs, “Housekeeper’s Chat,” and “Uncle Sam at Your Service.” FDA “Science Service” articles reprinted in popular magazines, with titles: “Patent Medicine Lies Cost Human Lives,” and “Must the Housewife Beware?” Speaking engagements with local chapters of the American Women’s Association, National Federation of Business and Professional Women, National Council of Jewish Women, National Home Economics Association, and National Parents and Teachers Association.

These were all avenues the agency sought to reach Americans about the potential dangers of medical products and cosmetics, as well as false and deceitful food packaging. And it was no coincidence that the nation’s homemakers, mothers, and shoppers-in-charge, at least as was implied in those days, were the target audience. Women, as they had already proven across American history, were vocal and effective agents in the crusade to protect their families’ and their children’s health. (Current alarms for children in the 1920s and 30s focused on trinkets or “prizes,” often made of lead, that were hidden inside bags of candy and caused choking, sometimes death…with no legal consequences for the manufacturer.)

A Chief Education Officer

The FDA’s first Chief Education Officer, Ruth deForest Lamb, was a proponent of the agency’s unvarnished truth approach—including broadcasting the horrific harms suffered by the public, as well as the shortcomings of an agency limited by an outdated 1906 law. The campaign to inform the public soon became synonymous with the one to spur Congress to pass new legislation that would grant the FDA the full and real capacity to protect the public who were at the center of its mission.

After numerous publicity engagements—including a two-and-a-half-minute film produced by Paramount, with voiceover from agency leadership talking about dangerous cosmetics, including the era’s vision-impairing mascara—the agency had so captivated the public, that it was receiving letters daily from private citizens across the country asking for guidance about the safety of drugs and cosmetics used in their homes.

Similar letters were also sent to lawmakers, and the mounting pressure to pass more extensive public health laws finally reached a critical mass in 1938, when on June 25, Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act into existence. This 1938 umbrella of laws continues to serve as the FDA’s primary authority in terms of regulating, and, more practically, ensuring the safety of, ALL foods and drugs, medical devices (from x-rays and defibrillators to mammography and CPAP machines), and cosmetics we consume and use in this country.

Sometimes Skeptical Public

While consumers still expect access to safe and effective drugs and medical devices, as well as safe and nutritious foods, their concerns have evolved, and so have their modes of processing and sharing information. Today’s FDA public affairs specialists, part of the agency’s primary field staff, the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA), have adapted to this new information landscape. They also recognize that fear, confusion, and distrust often stand in the way of efforts to advance U.S. public health.

Continuing in the tradition of Lamb and the many agency educators and consumer consultants before them, ORA’s Public Affairs Branch (PAB), a group of 19 frontline communications specialists located across the country and Puerto Rico, know these challenges better than anyone. In their engagements with the public—at schools, day care centers, churches, county fairs, and countless other venues, in addition to contact with Americans via phone, email and social media—PAB outreach staff have long appreciated the value of connecting with local communities, to build relationships and cultivate precious trust.

Forging Connections

Anitra Brown, who’s worked as an FDA public health communicator for 36 years now, says breaking down communication silos is tough, but rewarding. “The first step,” she says, "is just getting out there and getting to know the people in the communities we serve.” Transparency is another value she stands by, as well as being a patient and careful listener.

In contrast, Brown says, some public engagements offer more immediate impact, like helping school kitchens connect with best food safety practices, including support for students with food allergies. Building relationships with young people and college students, is another common theme for Brown and her colleagues who work closely with local schools and represent the agency at hundreds of career fairs across the country every year, to help attract interested candidates to FDA positions, ranging from food and drug inspectors and investigators to scientists.