Testimony | In Person

Event Title

Prioritizing Public Health: The FDA’s Role in the Generic Drug Marketplace

September 26, 2016

Statement of

Janet Woodcock, M.D.

Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Before the

Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies;

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

September 21, 2016

Introduction

Good morning Chairman Moran, Ranking Member Merkley, and members of the Subcommittee. I am Dr. Janet Woodcock, Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or the Agency). Thank you for the opportunity to appear today to discuss FDA’s role in executing the nation’s generic drug review program. I would also like to thank the Subcommittee for its past investments in FDA, particularly the Human Drugs program. The funding, most recently provided in FY 2016, has helped us meet the demands of our increasingly complex and diverse mission at home and abroad.

FDA recognizes the critical importance that generic drugs play in the U.S. healthcare system. At FDA, we recognize that when more than one version of a drug, especially when a generic version of a drug is approved, it can improve marketplace competition and help to provide additional options for consumers. Although FDA does not have a regulatory role in the pricing of drug products, we do play a critical role in ensuring patients have access to beneficial medicines. With this role in mind, and as I discuss more fully below, FDA is working hard to support the timely, scientific and efficient development of new generic drug products for the U.S. market.

The Rise of Generics

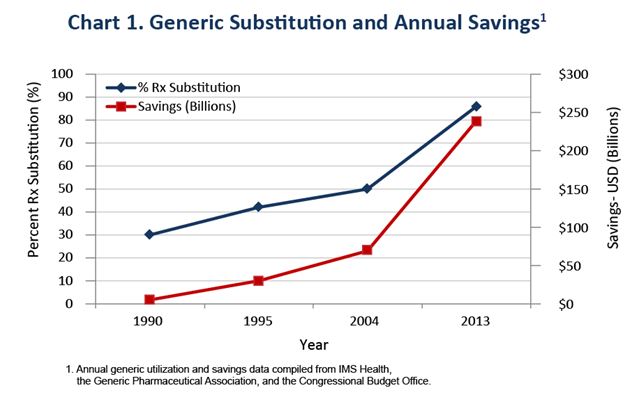

Recognizing the need to increase the availability of low cost generic drugs, over thirty years ago, Congress enacted the Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA).The Hatch-Waxman Amendments represent a great success in facilitating the widespread availability of safe, effective and high-quality generic drugs. According to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, generic drugs now account for nearly nine out of ten prescriptions dispensed in the United States and saved the U.S. health system $1.68 trillion from 2005 to 2014.

Abbreviated Pathways to Approval

The Hatch-Waxman Amendments formally establish two abbreviated approval pathways for drug products, while at the same time provide incentives for the continuing development of innovative new drug products. One of the two abbreviated approval pathways allows for the approval of Abbreviated New Drug Applications or ANDAs. Drugs approved under this pathway are commonly referred to as generics.

Unlike an innovator drug application, a generic drug application does not need to independently establish the safety or effectiveness of the drug. Instead, the generic drug has to show that it is the same as an innovator drug in several fundamental ways, such as in active ingredient, dosage form, route of administration, strength, and labeling (except for certain permissible differences in labeling); that the generic drug is absorbed and available at the site where it will act in the body at the same rate and to the same extent as the innovator drug (which is known as bioequivalence); and that it meets the same high standards for drug quality and manufacturing as an innovator product. If the ANDA meets these requirements, the generic applicant can rely on FDA’s previous finding of safety and effectiveness of the branded innovator drug, and need not conduct its own clinical investigations to establish safety or effectiveness.

FDA approval of an ANDA indicates that FDA considers the generic drug to be therapeutically equivalent to the innovator drug. This means that the Agency has concluded, among other things, that the generic and innovator drugs can be substituted with the full expectation that the generic drug will produce the same clinical effect and safety profile as the innovator product when administered under the conditions specified in the labeling. Therapeutic equivalence ratings are published by FDA in what is commonly known as the Orange Book. Although FDA does not itself determine when a pharmacy would substitute a generic drug in filling a prescription, state pharmacy laws and other regulations that determine substitutability often refer to these Orange Book ratings.

The Hatch-Waxman Amendments also established a second abbreviated pathway for drug applications. This pathway, commonly referred to as the “(b)(2) pathway,” can be thought of as a hybrid between the pathway for an entirely innovative product and the ANDA pathway for a generic drug. Unlike generic drugs, products approved under the (b)(2) pathway on approval are not presumed to be therapeutically equivalent to the innovator drug and, if a (b)(2) applicant seeks a determination of therapeutic equivalence, it must demonstrate this separately.

Keeping Up With Demand

Generic Drug User Fee Program

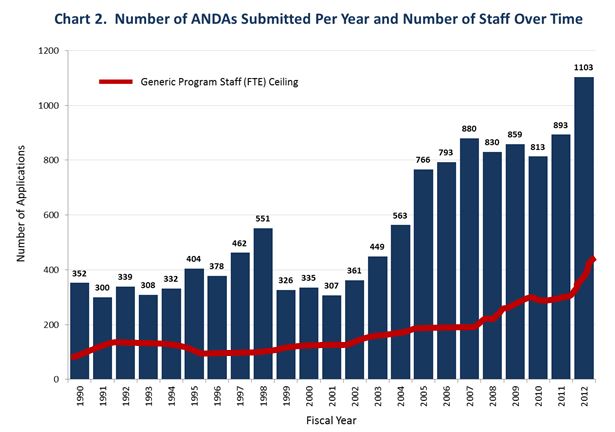

In response to this backlog issue, Congress enacted the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments of 2012 (GDUFA I), under which industry agreed to pay user fees each year of the five-year program and FDA committed to certain performance goals.

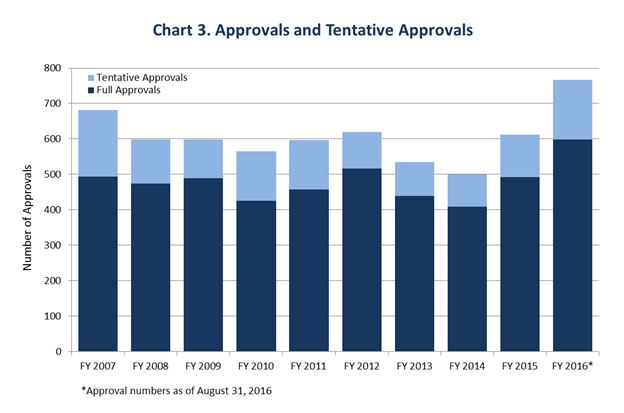

A major commitment of GDUFA I was to take a “first action” on 90 percent of the “backlog” applications, defined as pre-GDUFA applications pending before the Agency on October 1, 2012, by the end of Fiscal Year 2017. As of October 1, 2012, the backlog included 2,866 ANDAs and 1,873 prior approval supplements (PASs). A “first action” on an application means granting an approval or tentative approval, or, if there are deficiencies that prevent approval, identifying those deficiencies to the applicant in a complete response letter or in a refusal to receive the application. As of July 1, 2016, FDA had taken “first actions” on 90 percent of the backlog applications, achieving this performance goal 15 months ahead of schedule. In addition, FDA has met or exceeded all performance goals under GDUFA I with respect to ANDA’s submitted after GDUFA had commenced.

The cumulative result of all this effort is a huge increase in the productivity of the generics program. We ended last year at a new monthly high of 99 approvals and tentative approvals[1] in December. By July, with two months still remaining in this Fiscal Year, we had already achieved a new record of 702 approvals and tentative approvals.

Some of the backlog applications, mentioned above, had been pending or in review for a long time prior to GDUFA. At this point in time, as FDA acts on a backlogged application, the “time to approval” of such application will be recorded as, at minimum, 47 months (i.e., we are now three years and eleven months (47 months) into GDUFA implementation).

Applications submitted in Fiscal Year 2016 have a GDUFA first-action goal date of 15 months. For Fiscal Year 2017, which begins in 10 days, an incoming ANDA will receive a 10 month GDUFA goal date. If the ANDA is for a priority product – such as a first generic – its review will be further expedited. This year, we have achieved a record number of ANDA approvals and a record number of first cycle approvals.

Deep, foundational restructuring

These successes were achieved by restructuring our organization for generic drug review, to build a modern generic drug program. This involved major reorganizations. We reorganized the Office of Generic Drugs and elevated it to a “Super-Office” status, on par with the Office of New Drugs. We established a new Office of Pharmaceutical Quality to integrate the quality components of the review.

We developed an integrated informatics platform to support the generic drug review process. This platform is a significant improvement over our earlier fragmented, legacy systems, and has enhanced our productivity.

We hired and trained more than 1,000 new employees, achieving our GDUFA hiring goals well ahead of schedule.

FDA Creates a Pathway for Generics Development

In addition to the work that FDA does with individual companies to support their development of specific products, FDA also works to create a publicly available roadmap describing what companies need to do to bring various types of medical products to market.

FDA is continuing to develop, publish, and update guidance documents, which are a kind of roadmap for industry sponsors, explaining FDA’s recommendations for the kind of information that should be included in a marketing application. Guidance documents can provide vital information to drug and device developers for a class of products.

FDA also recognizes that for more complex products, in addition to guidance, one-on-one advice may be needed so FDA can address technical and regulatory questions about the pathway to market. Such meetings occur now for both new drugs and generic drugs under development. In addition, FDA regularly responds to specific product-development questions from industry that FDA answers in writing to help companies develop generic drug applications through the process known as Controlled Correspondence. We hope to expand our ability to engage with generic product sponsors through a reauthorization of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (or GDUFA II), where complex product meetings have been described as a key provision of the proposed program.

Further, FDA prioritizes the resources we make available to focus on areas of high public health needs. For example, FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) has a prioritization and expedited review policy for certain generic drug applications. The policy is set forth in a publicly available document called a Manual of Policy and Procedures[2] (MAPP), which can be found on the FDA website. Pursuant to OGD’s prioritization policy, ANDAs for drugs that have “first filer” status or that otherwise are eligible to be the first generic approved are prioritized and given expedited review.

Each of these, and other efforts of FDA, help clarify our expectations and prioritizations concerning specific products so industry can develop and obtain approval of generic versions of branded drugs more quickly.

While FDA is working to lay out a roadmap to support efficient development of complex products, we cannot, and will not, allow a substandard product to come onto the market. In addition to working to assure the safety and efficacy of drugs, it is critical that they be manufactured to high quality standards to assure they can be used safely by patients when they are needed. FDA’s new Office of Pharmaceutical Quality plays a critical role in ensuring the quality of both generic and new drugs.

FDA’S Role in the Intellectual Property Landscape

Although FDA can and does encourage generic drug development and has and continues to streamline and improve its review and approval of generic drug applications, the decisions of whether to seek approval for a proposed generic drug and whether to market an approved generic drug are controlled by the generic drug industry. Further, the extent to which the approval or marketing of generic drugs is delayed because of intellectual property rights or marketing exclusivities is largely controlled by the innovator-drug manufacturers and others that hold those rights.

With respect to patents, FDA has only a “ministerial” role. As noted earlier, the Hatch-Waxman Amendments sought to balance two competing goals: (1) increasing the availability of generic drugs, and (2) increasing incentives to develop new and innovative drug products. In addition to creating certain marketing exclusivities, the Hatch-Waxman Amendments established a set of procedures intended to align the generic drug approval process with an opportunity for the owners of innovator drugs to assert certain rights for patents covering the innovator drug before generic drug approval. While FDA plays a role in this process, our role is very limited.

First, sponsors of innovator drugs must submit to FDA information regarding certain patents related to their products. FDA lists these patents in the Orange Book. In any application that seeks to rely on a previously approved NDA, which includes (b)(2) applications and generic drug applications, the applicant must describe whether it intends to challenge those listed patents in court. Specifically, the applicant may inform FDA that there are no patents listed, or that the applicant is not seeking approval until after a patent listed in the Orange Book expires. Alternatively, an applicant can also notify FDA that it intends to challenge a listed patent as invalid, unenforceable or not infringed. Where an applicant seeks to challenge a patent, the applicant is required to submit to FDA certain information regarding its patent challenge and any resulting patent litigation as part of its application; but, the challenge and litigation take place between the applicant and the patent holder(s) in the courts and outside FDA’s regulatory authority. If an applicant is challenging a patent, the law describes when FDA can approve the application in a complex scheme, including a potential 30-month stay of an approval if the ANDA applicant is sued soon after making the patent challenge. In each case, the ANDA applicant’s decision regarding whether to challenge a patent, and when applicable, the innovator sponsor’s response, and the court’s decision on the patent can affect when FDA may (and may not) approve the generic drug application.

As drug applicants often publicly acknowledge, they routinely take the intellectual property rights of previously approved drugs into account when making determinations regarding the design and development of their proposed drugs. While our approval standards are the same whether or not an applicant designs its proposed product around a competitor’s intellectual property rights, the proposed products that FDA receives for review and consideration for approval are no doubt impacted by patent considerations.

Overview of the Epinephrine Auto-Injector Market

Epinephrine auto-injectors, with the most widely used and recognizable product being Mylan’s EpiPen, are a critically important, and potentially life-saving, product for patients who suffer from a severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis. These products are considered combination products since they consist of a drug component (epinephrine) and a device component (auto injector). When a patient requires the medication, seconds count, and the epinephrine auto-injector must work every single time. To ensure this, it is critical that both the drug, and the device that delivers the drug, perform as designed.

At FDA, we are aware of the recent spike in the price of the EpiPen. FDA has approved four epinephrine auto-injector products to treat anaphylaxis; two of which are currently on the market. While there are currently no FDA-approved generic epinephrine auto-injectors, we stand ready to quickly review additional applications that come to us from both generic and innovator drug companies.

Mylan’s EpiPen is the market leader for epinephrine auto-injectors in the United States, and Mylan has recently publicly announced they also will offer an authorized generic version[3] to be available in the near future. Another firm, Amedra holds an approval for Adrenaclick, which is also an epinephrine auto-injector. Currently, while the Adrenaclick brand name product is not being marketed, Amedra is marketing its own authorized generic version of the drug. Amedra also previously marketed Twinject, but this product has been discontinued. Finally, FDA also approved Auvi-Q as an epinephrine auto-injector, although this product was voluntarily recalled from the market in 2015 by Sanofi. We note that Auvi-Q was recently purchased by Kaleo, though this product has not yet returned to the market. In support of increasing the number of epinephrine auto-injector products on the market, FDA is committed to working with both Amedra and Kaleo to facilitate greater availability of their products.

Conclusion

Thank you for your interest in the important topic. FDA takes seriously its role in executing the nation’s generic drug program, and we understand the importance of generic products in the U.S. marketplace. We anticipate that our ongoing efforts to continue to improve generic drug development will provide dividends in both protecting the health of Americans as well as in cost savings long into the future. We hope that our efforts, coupled with the work of other groups that also have roles to play, will continue to ensure medications are readily available to patients. I am happy to answer any questions.

[1]. Tentative approval applies if a generic drug product is otherwise ready for approval before the application may otherwise be approved because of issues related to any patents or exclusivities accorded to the reference listed drug product. In such instances, FDA issues a tentative approval letter to the applicant. FDA delays final approval of the generic drug product until all patent or exclusivity issues have been resolved. A tentative approval does not allow the applicant to market the generic drug product.

[2]. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/

[3]. An ‘authorized generic’ is made under the brand name’s existing new drug application using the formulation, process, and manufacturing facilities approved for use by the brand name manufacturer. The labeling is changed to remove the brand name or other trade dress. An authorized generic is not synonymous with an FDA-approved generic, the latter of which requires a separate application and approval from that of the brand name product.