The WTO’s Decision on Australia’s Plain Packaging Tobacco Measures Explained

FROM A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

By Joseph Rieras, J.D.

December 16, 2020

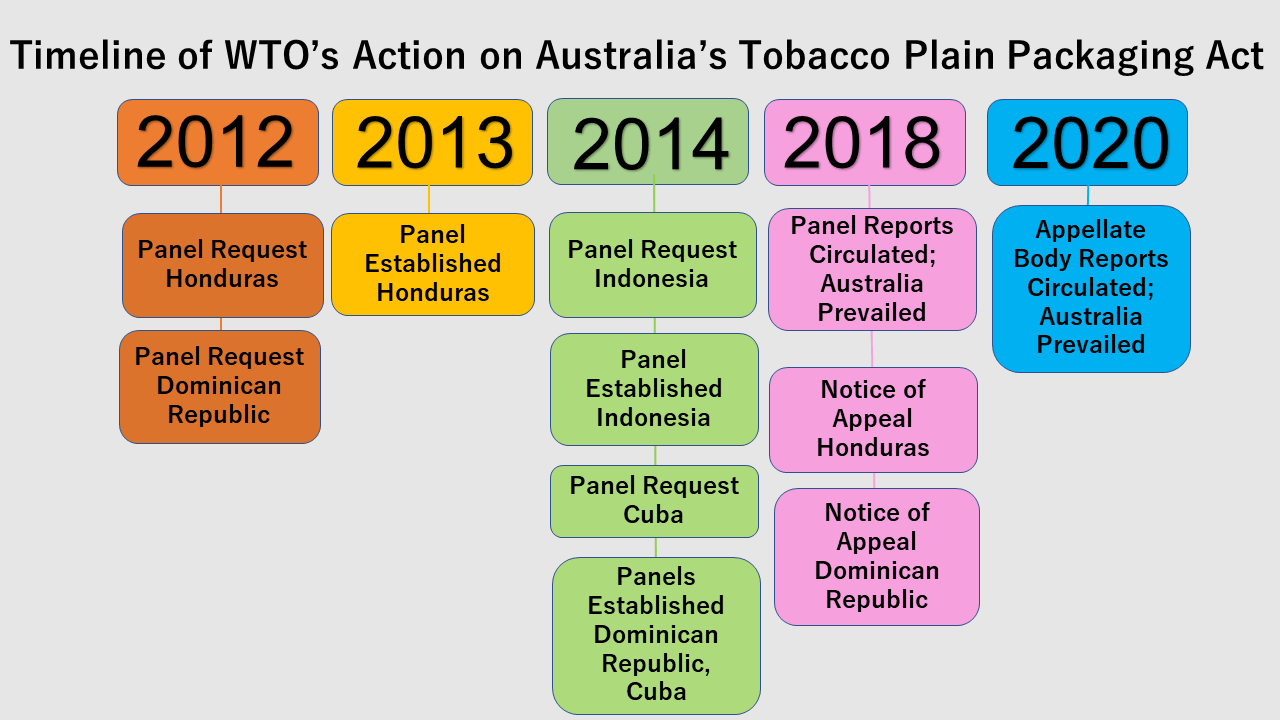

An Australian law requiring plain packaging on tobacco products was upheld by the World Trade Organization (WTO) earlier this year, rejecting appeals from the Dominican Republic and Honduras.[1] This decision is of great interest to public health experts in the United States and elsewhere who view comprehensive measures that include regulation of tobacco packaging as an effective way to meet important public health objectives, such as reducing smoking, especially by teens.

The WTO Appellate Body upheld the original panel’s conclusions that Australia’s Tobacco Plain Packaging Act as well as its Tobacco Plain Packaging Regulations (Plain Packaging Measures) make a meaningful contribution to Australia’s legitimate objective of reducing the use of, and exposure to, tobacco products. Further, it said that the public health consequences of not fulfilling this legitimate objective are particularly grave; and that the complainants failed to demonstrate that proposed alternative measures would be less-trade-restrictive or would make an equivalent contribution to Australia’s legitimate public health objectives.[2]

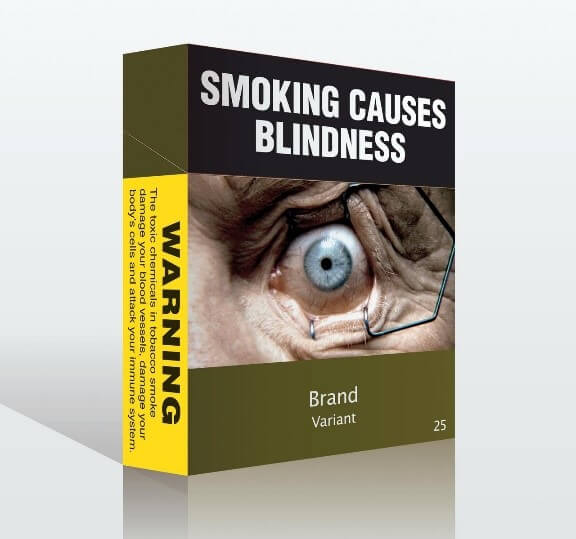

The Plain Packaging Measures, established in Australia in 2011, [3] directed that brand images, display logos and promotional text be removed from cigarette packages - doing away with the use of attractive colors, eye-catching designs, and engaging characters on tobacco packages that public health experts argued made smoking more appealing, and attracted new customers, especially teens.

Australia applied plain packaging in conjunction with graphic health warnings (GHWs), which were not challenged in the dispute. The plain packaging was on the top, side, and base of the pack. The GHW was on the front of the pack. The Plain Packaging Measures formed part of Australia’s comprehensive tobacco control scheme, which included taxation measures and educational campaigns.

Image provided by the Australian Government of a proposed 'plain-packaged' cigarette packet.

WTO Dispute Settlement Process

The WTO operates a global system of trade obligations, acts as a forum for negotiating trade agreements and settles trade disputes between its more than 160 members. Dispute settlement is a three stage process: consultations; panel proceeding, and (if requested) Appellate Body proceeding; and, if needed, implementation to bring inconsistent measures into compliance with WTO obligations. Honduras filed the first consultations request in April 2012 (followed by the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Indonesia). From beginning to end, this dispute lasted eight years, making it one of the longest in WTO history.

WTO Legal Framework

Regulations by public health authorities are subject to numerous WTO obligations. Among such obligations, WTO members generally must ensure that a regulation is not more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfill a legitimate objective, for example, protecting human health and safety.[4] Assessing whether a regulation meets the WTO requirements involves an analysis of three factors: the degree to which the law and regulation, (i.e., in this case, plain packaging) contributes to a legitimate objective; the trade-restrictiveness of the measure; and the nature of the risks and the gravity of consequences if the objective is not fulfilled.[5]

Let’s take each factor in turn to see how the original panel analyzed this case.

Was the objective pursued a legitimate objective?

It was undisputed that the objective of Australia’s regulations was to protect public health by controlling the use of tobacco products. Australia argued that its objective was to “reduc[e] smoking rates in Australia by reducing the appeal of tobacco products, increasing the effectiveness of graphic health warnings, and reducing the ability of packages to mislead consumers about the harms of smoking.”[6] The complainants attempted to define Australia’s objective narrowly as “reducing smoking prevalence.”[7]

The panel found the objective to be related to the protection of human health, in particular “to improve public health by reducing the use of, and exposure to, tobacco products.”[8] The panel also found that Australia’s objective was legitimate.[9] Viewing Australia’s public health objective broadly was a pivotal decision that effected the panel’s other findings.

To what extent did the measures contribute to the objective?

The complainants argued that the measures could not contribute to Australia’s objective citing evidence showing that Australia’s measures had not in fact reduced smoking prevalence. Australia responded that its measures were based on sound evidence, and that the available evidence confirmed that the Plain Packaging Measures were indeed contributing to their broader objective.[10] The panel sided with Australia, saying that “the evidence before us, taken in its totality, supports the view that the TPP measures, in combination with other tobacco-control measures maintained by Australia (including enlarged GHWs introduced simultaneously with TPP), are apt to, and do in fact, contribute to Australia's objective of reducing the use of, and exposure to, tobacco products.”[11]

Are the measures trade-restrictive?

The panel concluded that Australia’s measures restrict trade “by reducing the use of tobacco products, they reduce the volume of imported tobacco products on the Australian market, and thereby have a ‘limiting effect’ on trade.”[12] Here, the panel seemed to say that if a measure is successful in contributing to a public health objective, then, in this case, that is evidence that it is trade-restrictive. What are the consequences of non-fulfillment?

The panel explained that not fulfilling the objective would pose a public health risk since the use of and exposure to tobacco products would not be reduced.[13] Further, “it is widely recognized, and undisputed in these proceedings, that the public health consequences of the use of, and exposure to, tobacco, including in Australia, are particularly grave.”[14] Therefore, the panel ruled that the public health consequences of not fulfilling the objective were particularly grave.

Were less-trade-restrictive alternative measures reasonably available?

The complainants offered four less-trade-restrictive alternatives to plain packaging that might make an equivalent contribution to Australia’s objective: 1) increase the minimum age to buy tobacco products from 18 to 21 years old; 2) increase the tax on tobacco products; 3) create more effective social marketing campaigns to discourage the use of tobacco products; and 4) establish a complicated “pre-vetting process” where the packaging of each tobacco product would be assessed (rather than a comprehensive regulation of tobacco packaging).

Notably, the panel observed that when a country “maintains the measure at issue as one ‘element[] of [a] comprehensive policy,’ substituting another ‘element of [that] comprehensive policy’ for the measure at issue may ‘weaken the policy by reducing the synergies between’ the components of that package, as well as its total effects.”[15] The panel ultimately held that none of the options were less-trade-restrictive alternative measures that would make an equivalent contribution to Australia’s objectives.

Conclusion

In light of these views, the WTO Appellate Body concluded that the Plain Packaging Measures were consistent with WTO obligations relating to public health restrictions.[16] A few points emanating from this dispute are noteworthy. The panel rejected the argument that scientific publications presented as evidence in dispute settlement proceedings can only be validly considered by a panel if the complete underlying research data is also made available.[17] Because public health authorities rely on scientific publications to support their actions, this evidentiary finding is important.

Generally, addressing public health issues with comprehensive policies is more effective than individual, piecemeal measures. The panel’s statement on comprehensive policies and their constituent elements supports this approach. Also, while the measures involved tobacco packaging regulations, the panel’s reasoning could be applied to support other public-health-related packaging schemes, such as nutritional labeling schemes. In the end, the panel did not upset Australia’s approach to tobacco plain packaging regulation, and this was a good result for public health authorities.

Senior Advisor Joseph Rieras, J.D., in the Office of Trade, Mutual Recognition, and International Arrangements, focuses on trade negotiations and issues governed by the TBT Agreement.

[1] Panel Reports, Australia – Certain Measures concerning Trademarks, Geographical Indications and other Plain Packaging Requirements applicable to Tobacco Products and Packaging, WT/DS435/R, Add.1 and Suppl.1; and WT/DS441/R, Add.1 and Suppl.1 (adopted June 29 2020, as upheld by Appellate Body Reports WT/DS435/AB/R, and WT/DS441/AB/R).

[2] In the original proceeding, Cuba and Indonesia also filed complaints but, unlike the Dominican Republic and Honduras, they did not lodge an appeal.

[3] Other countries, noticeably the UK and France, have adopted similar laws and rules since then.

[4] Article 2.2 of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Agreement).

[5] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.184.

[6] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.214.

[7] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.214.

[8] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.232.

[9] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.251.

[10] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.485.

[11] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.1025.

[12] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.1208.

[13] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.1297.

[14] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.1310.

[15] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.1384.

[16] On appeal, the WTO Appellate Body found errors in the Panel’s analysis regarding the contribution of two of the alternative measures to Australia's objectives. But the WTO upheld the ultimate conclusion that these suggested alternatives were not less trade-restrictive alternatives; and thus, the Australian measures are consistent with WTO rules.

[17] Australia – Plain Packaging (Panel Reports), para. 7.513.