The American Chamber of Horrors

Consumers’ Research, a pioneer in US consumer advocacy, launched the opening volley in the consumer war with publication in 1933 of 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs by Arthur Kallet and Frederick Schlink. [43] To illustrate the need for a new law, FDA officials had assembled a collection of problem products. Initially merely an exhibit for Congress, publication of Kallet and Schlink’s book elevated the collection into a public relations tool, particularly when Eleanor Roosevelt, a tireless advocate of causes, toured the exhibit.[44] A reporter accompanying her in 1933 dubbed it ‘The American Chamber of Horrors’ (Figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4 Commissioner Larrick explaining the Chamber of Horrors exhibit.

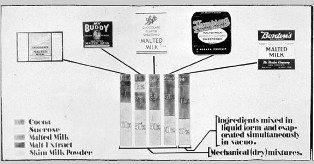

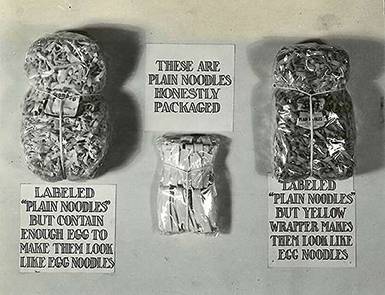

Even by the standards of the day, the ‘Chamber of Horrors’ was not an exciting exhibit. It was, however, both truthful and provocative, persuading many companies to change their ways just to secure removal from the exhibit. A major part of the food portion of the exhibit was devoted to explaining the need for various kinds of food standards. Products such as malted milk (Figure11.5), egg noodles (Figure 11.6), and jarred chicken products (Figures 11.7–11.8) all required standards of identity in order for consumers to know what they were buying, since neither price nor packaging were reliable guides.

|

|

|

Figure 11.5 This exhibit emphasied the need for a definition or standard of identity for malted milk.

|

Figure 11.6 Deceptive packaging: egg noodles.

|

|

|

|

Figure 11.7 Deceptive packaging; jarred chicken, dark meat hidden under the label.

|

Figure 11.8 Exhibit illustrating the need for compositional standards.

|

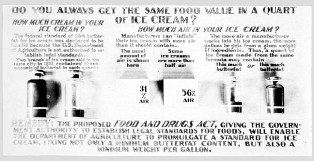

One of the most problematic products for advocates of food standards was ice cream (FIGURE 11.9). Fat was considered the most valuable ingredient, and this ingredient was widely variable. Before home freezers were available, most ice cream was locally produced and consumers were often loyal to the ice cream to which they were accustomed, regardless of its fat content. Regulators believed labelling the cream content was the best way to insure that the consumer got what was expected.

Figure 11.9 This image shows how the manufacturer of ice cream

can fool the consumer in their labelling of the cream content.

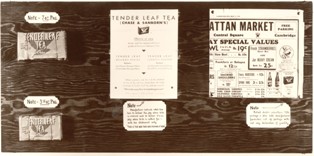

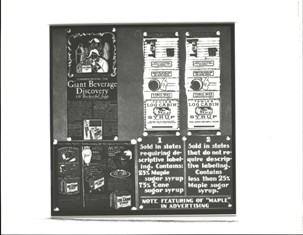

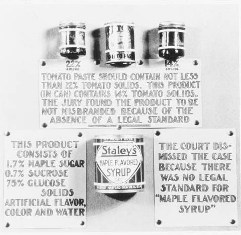

Several panels of the exhibit explained both the McNary-Mapes amendment (Figure 11.10) and the need to expand its provisions to other foods. The ‘distinctive name proviso’ had created immense confusion over the labelling and adulteration of maple syrup under the 1906 Act (Figure 11.11). In one panel, regulators tried to show that the ‘descriptive labelling’ advocated by some manufacturers as a model for the new statute, would still not correct basic deception in the marketing of maple flavoured syrups (Figure 11.12).

Figure 11.10 Packed in glass like these examples, it is easy to pick the higher quality product.

This exhibit makes the case for standards of quality.

|

|

|

Figure 11.11 Shows that the same products are labeled differently in states that require descriptive

|

Figure 11.12 No legal standard for tomato paste or for maple flavoured syrup.

|

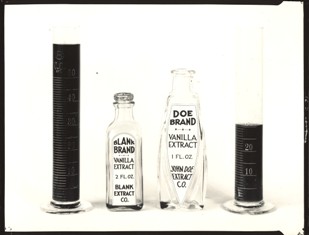

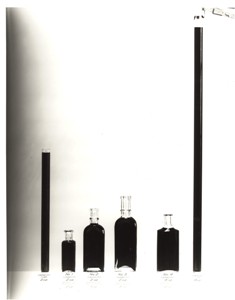

Finally, the Chamber of Horrors dramatically illustrated the use of deceptive containers. McNary-Mapes had eliminated some deceptive packaging in the canned foods industry (Figures 11.13 and 11.14), but deceptively large boxes, some with false bottoms (Figure 11.15), and bottles clearly designed to deceive, remained an important problem. Fill of container was an important economic issue. Expensive flavouring extracts and teas were easy targets.

|

|

|

Figure 11.13 Grated cheese packaging before and after the McNary-Mapes amendment. |

Figure 11.14 Grated cheese packaging before and after the McNary-Mapes amendment.

|

Figure 11.15 Deceptive packaging with false bottoms continued to be a problem.

|

|

|

Figure 11.16 Vanilla extract packaging before and after the McNary-Mapes amendment.

|

Figure 11.17 Deceptive packaging with false bottoms continued to be a problem.

|

Figure 11.18 Deceptive bottles used for marketing flavourings. |

Figure 11.19 Bottle sizes and shapes obscure the true contents of the bottles.

|

The Chamber of Horrors was visually persuasive, illustrating vividly the old clichés about the worth of a picture and the one bad apple that spoils the barrel. The food industry, its trade associations and its lawyers, could and did argue that these examples were unusual, even rare, but the fact that such products existed and were easily recognised by consumers accustomed to trusting brand names made the case for regulation all the more compelling. Consumers, moreover, were more likely to accept the need for all standards proposed in the exhibit than to quibble over the merits of quality standards as opposed to standards of identity and fill of container.

The popular exhibit was displayed at the White House and the Chicago World’s Fair, inspiring FDA’s Chief Educational Officer, Ruth deForest Lamb, to employ a leave of absence to write a book by the same title. Where Kallet and Schlink simply condemned governmental inaction, Lamb exposed the legal weaknesses in the 1906 Act that frustrated government efforts. She also documented the less than forthright tactics employed by many industries, advertisers, trade associations, and lawyers to thwart enactment of effective regulation. Lamb was hardly a disinterested observer, but she also advocated a different kind of consumerism. Kallet and Schlink portrayed consumers as rather hapless victims, but she cleverly dedicated her book to the host of women’s organisations that were actively and effectively sponsoring the new law being debated in Congress. In the American Chamber of Horrors, Lamb’s chapter on food standards was apparently persuasive. Lamb herself was pleased at the book’s reception remarking that

… the only thing that makes me apprehensive is the number of endorsements from the trade press ... When the ‘American Grocer’ appears to endorse my chapter on standards I am inclined to think there is something wrong with the chapter.[45]

Late nineteenth century reform journalists known as muckrakers had been influential in persuading the public to support the 1906 Act. Likewise, consumer advocates such as Lamb, Kallet and Schlink proved equally influential in the legislative battle to enact a new food and drug law and were soon nicknamed ‘guinea pig muckrakers’.

[43]A. Kallet and F. Schlink, 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs: Dangers in Everyday Foods, Drugs, and Cosmetics, New York, Vanguard Press, 1933.

[44]Lamb claims the exhibit was first assembled in 1912 for hearings on the Sherley Amendment. Lamb, op. cit., p. 133.

[45]R. Lamb to W. Wharton, frontispiece of presentation copy of American Chamber of Horrors, n.d., FDAHO