The Long Struggle for the Law

By James Harvey Young

The Dining Room of "The Poison Squad"

Many forces combined to create the need for the 1906 Food and Drugs Act. James Harvey Young traces the history of the law and the conditions that led to its enactment. The author is professor of history at Emory University and is the author of many books and articles on food and drug regulatory history.

On June 30, 1906, a broiling day in Washington, President Theodore Roosevelt went to the Capitol to sign into law nearly a hundred bills hurried through the Congress as its session came to an end. Among them was one passed the day before by both Senate and House in a form agreed to in conference committee, the Food and Drugs Act. Although a latecomer to the cause of a pure food law, Teddy Roosevelt had used his weight decisively in 1906 to ensure that this time Congress would not adjourn, as so often before, leaving such legislation languishing.

The 1906 law's relevant background in America starts with colonial food statutes concerned with bread and meat. The first national law came in 1848 during the Mexican War. It banned the importation of adulterated drugs, a chronic public health problem that finally got Congressional attention.

The first prolonged and impassioned controversy in the Congress involving a pure food issue took place in 1886, pitting the reigning champion, butter, against a challenger, oleomargarine. Butter won, and oleomargarine was taxed and placed under other restraints that persisted on the Federal level until 1950. The debate in 1886 between the defenders of a natural food and those of its alleged artificial substitute centered not only on matters of vested interest, but also pondered concerns about the public health, issues of governmental authority, and the myths in which were enshrined the meaning of the American experience. Such themes re-echoed in Congressional chambers as Senate and House later debated broader bills to control food and drugs in interstate commerce. The first broad bill had been introduced in 1879, although a decade passed before Congress displayed serious interest.

One way to structure the intricate pure food story is to consider seven "C's." These are change, complexity, competition, crusading, coalescence, compromise, and catastrophe.

Change means the turbulent readjustments in the American way of life that occurred as society industrialized and urbanized. Accompanying, indeed fostering, such modifications came a revolution in science and technology, with its planned and also unforeseen consequences. Discoveries in chemistry, for example, led to new synthetic medicines and altered radically both the growing and the processing of food. Transportation developments brought processed food to an increasingly national market, making the growth of giant cities possible. The residents of those cities lost the ability villagers had possessed of being first-hand judges of the food they ate.

Some of the food that city dwellers took from cans and jars deviated greatly from village garden produce. Chemicals could be used to heighten color, modify flavor, soften texture, deter spoilage, and even transform ingredients like apple scraps, glucose, coal-tar dye, and timothy seeds into concoction labeled strawberry jam. Adulteration might be an age-old problem, but, in the words of a Senate report in 1890, "it has only been since the great opportunity for fraud provided by modern science ... that the sophistication of articles of commerce has reached its present height."

The second "C" stands for complexity. All of man's concerns grow more complex, and a particular kind of complexity became wedded to the question of how the Federal Government might confront deceptions and hazards in the food and drug supply. A few products, like oleomargarine and tea, were controlled by individual laws. Mainstream legislation proposed in the Congress, however, was complex, omnibus bills encompassing food and drink and drugs. All food and drink and most drugs entered the body through the mouth, and all were subject to similar adulterations. So it was natural to face the problem all at once. British precedent pointed in this direction, a factor of consequence in the campaign for an American law. Not only did drafters of both State and Federal bills turn for guidance to British experience; American businessmen and farmers engaged in exporting food frequently felt the bite of, and hence became keenly aware of, British law. Broad omnibus bills meant that many interest groups would be subject to the law's provisions, with producing and processing units located in every congressional district. Such a circumstance made inevitable a long and tortuous legislative process.

Competition in the marketplace, the third "C," lay behind the earliest omnibus bills. By a sort of Gresham's law, adulterated foods that could be sold more cheaply threatened to drive out sounder fare. Alarmed, the more reputable wing of the food industry appealed to the Congress for help and gave counsel to that body. In 1879, a trade press editor persuaded his brother-in-law, a wholesale grocer, to put up a prize for the best draft statute submitted to the National Board of Trade. The prize was won by an English food analyst who adapted the 1875 British law to American circumstances. The Board of Trade prize committee revamped the analyst's proposal, and in 1881 a Connecticut congressman introduced the committee draft as a bill.

Throughout the succeeding quarter of a century, the pain of what they deemed unfair competition kept business groups reviving their appeals to the Congress for the protection that would be afforded by a national law. As the 1890 Senate Report put it, faith in commercial integrity, the "very foundation of trade," was being undermined. The proliferation of State laws containing contradictory provisions made action on the national level the only sensible solution. "As it is now," a maker of jam complained, "we have to manufacture differently for each state." A national statute might set a standard States would follow.

Farmers in agrarian States, as their campaign against oleomargarine demonstrated, also felt aggrieved by what they thought was unfair competition. Shady processors adulterated fertilizers, deodorized rotten eggs, revived rancid butter, substituted glucose for honey. Farmers began to learn about such deceptions from a new breed of agriculture chemists, often trained in Germany, located in State officialdom and helped by Federal funds. These chemists could apply their scientific skills to expose the work of chemists employed by industry to depreciate food products, as the Senate Report put it, in "a greed for gain." Exposure bulletins agitated farmers, who increased their demand for a protective national law.

Those threatened by the new competition could bring omnibus bills before the Congress but could not secure their passage. At the height of the Populist movement in 1892, agrarian pressure got one bill through the Senate, but divided business interests and constitutional scruples blocked it in the House. During the remaining years of the 19th century, no broad pure food bill made it through either chamber of Congress. Competitors spoke with conflicting voices, all heard in Washington. The broad public was not yet very much aroused.

When the first omnibus bills began to appear, George T. Angell represented the prime example of crusading, the fourth "C." A lawyer whose claim to public recognition lay in his fight against cruelty to animals, Angell advocated rigorous regulation of all food processors, charging that dire hazards to health plagued every marketplace. Angell thought business-sponsored bills were too unmindful of the consumer, whereas businessmen thought Angell a devilish alarmist. Later, such committed champions of the consumer as the National Consumer League and the General Federation of Women's Clubs joined the crusade for a tough law, and so, too, with the new century, did muckraking journalists.

Harvey W. Wiley came to be the leader of the "pure food crusade." A chemist and physician, State chemist of Indiana and professor at Purdue University, Wiley went to Washington in 1883 as chief chemist of the Department of Agriculture. He made the study of food adulteration his bureau's principal business, at first merely outraged by what he deemed essentially harmless fraud. In time, sensing real threats to health, Wiley could express himself in writing, conversation, and oratory with vividness, clarity, homely wit, and moral passion. He toured the country making speeches, every rostrum a pulpit for the gospel of pure food.

Besides crusading for a law, Wiley played other indispensable roles. He sought to organize his allies and recruits into a coalition which might be powerful enough to move Congress to action. Coalescence is the fifth "C." Wiley forged bonds among agricultural chemists, State food and drug officials, women's club members, the medical profession, sympathetic journalists, the reform wing of business, and favorably disposed members of Congress. This was a mighty effort requiring the utmost in patience and diplomacy.

Could all factions favoring a law in principle, especially elements from the complex business community, be brought to agreement in support of a specific bill? Compromise, the sixth "C," seemed to offer a route to success. In three National Pure Food and Drug Congresses held between 1898 and 1900, Wiley sought to work out agreements in the private sector that might smooth passage of a law. The magnitude of the task is suggested by a look at some of the groups represented: trade associations, for example, of millers and brewers, marketers of butter and makers of candy, fishermen and beekeepers, wholesale and retail grocers, wholesale druggists, and proprietary medicine manufacturers. Also present were representatives from State and Federal agencies, farm organizations, professional societies of chemists and pharmacists, even the National Peace Conference and the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Delegates labored diligently and made much progress, but not enough. Some differences seemed too wide to bridge, like those between dairy and margarine interests, between makers of alum and cream-of-tartar baking powders, and between straight whiskey distillers and blenders. As the new century dawned, efforts at compromise continued, but in the halls and committee rooms of Congress.

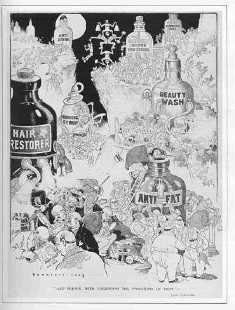

In some ways the constantly revised version of the battered basic bill became more rigorous because crusading accelerated. Increasing criticism by the revitalized American Medical Association and by journalists of patent medicine abuses, for example, brought controls aimed at nostrums into the bill -- at the cost of drug trade support. And Dr. Wiley's sober scientific effort, begun in 1902, to test his hypothesis that chemical preservatives in processed foods posed threats to health, reported flamboyantly in the press as "Poison Squad" experiments, made a growing audience aware of adulteration and of the pending bill.

At the turn of the century, false hopes were sold with vigor similar to today. This cartoon from the April 29, 1909, Life magazine illustrates the point.

Twice an omnibus bill passed the House of Representatives under the aegis of its managers, Congressmen from western States in which agricultural interests were dominant. But business lobbies, especially whiskey rectifiers and proprietary drug manufacturers, despite all the power of Wiley's coalition, kept the pure food bill from becoming law. The opposition was more silent than outspoken, making its weight felt through parliamentary obstructionism. Southern conservatives did openly challenge the constitutionality of such legislation. "The Federal Government," opined a Georgia congressman, "was not created for the purpose of cutting your toe nails or corns."

In the end it took the seventh "C," catastrophe, to fuel the final compromise and get the law enacted. The catastrophe concerned meat. Meat had been separated from other food for special legislative treatment in 1890 and 1891. Federal inspection had been started not to safeguard the American diet but to reassure European nations that had banned importation of American pork on the exaggerated charge that it had caused epidemics of trichinosis. A newspaper scare closer to home arose during the Spanish-American War, when packers were blamed with shipping "embalmed beef " that sickened the troops. Investigation traced some of the trouble to the rapid growth of bacteria in meat exposed to the hot Cuban sun.

Then, in 1906, Upton Sinclair published his socialist novel, THE JUNGLE, aimed, as he later said, at people's hearts but hitting their stomachs instead. His few pages describing filthy conditions in Chicago's packing plants, widely reported and confirmed by governmental inquiry, cut meat sales in half, angered President Roosevelt, and pushed a meat inspection bill aimed at protecting the domestic market through the Congress.

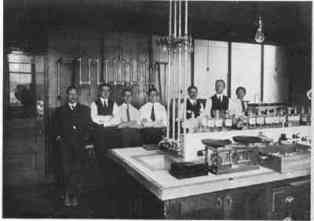

Inspectors from the Bureau of Chemistry's office in Indianapolis, 1909.

The President, in December 1905, had at long last sent a terse message to the Congress urging it to enact a pure food bill. The Senate had responded. Amidst the meat crisis, when the House leadership seemed again determined to give the food measure the silent treatment, Roosevelt called the speaker in and insisted that the bill be brought to the floor. Wiley energized his coalition to a last burst of pressure. Committees engaged in a final flurry of compromise. And the bill became law.

The 1906 law forbade interstate and foreign commerce in adulterated and misbranded food and drugs. Offending products could be seized and condemned; offending persons could be fined and jailed. Drugs had either to abide by standards of purity and quality set forth in the UNITED STATES PHARMACOPEIA and the NATIONAL FORMULARY, works prepared by committees of physicians and pharmacists, or meet individual standards chosen by their manufacturers and stated on their labels. An effort failed to place in the law food standards as defined by the agricultural chemists, but the law prohibited the adulteration of food by the removal of valuable constituents, the substitution of ingredients so as to reduce quality, the addition of deleterious ingredients, and the use of spoiled animal and vegetable products. Making false or misleading label statements regarding a food or a drug constituted misbranding. The presence and quantity of alcohol or certain narcotic drugs had to be stated on proprietary labels.

A Bureau of Chemistry laboratory, 1911.

The law sought to protect the consumer from being deceived or harmed, mainly by following a favorite assumption that the average man was prudent enough to plot his own course and would avoid risks if labeling made him aware of them. In this spirit, some ardent pure food advocates predicted that the law would usher in the millennium. Defeated business interests, on the other hand, congratulated themselves that the bill's strictures, largely through their own lobbying, had not turned out to be tougher than they were. Anxiously these interests waited to observe the temper of enforcement. Dr. Wiley believed that, for a pioneering statute, the measure had turned out rather well. He felt optimistic that Congress would readily remedy weaknesses in the law which he immediately recognized and which he knew would be further revealed by enforcement efforts. Although some fuzziness existed in the administrative provisions, the law gave Wiley's Bureau of Chemistry the task of spotting violations and preparing cases for the courts. Both a crusader and compromiser in the long struggle to secure the law, Wiley determined, now that Congress had put power into his hands, to wear his crusading armor and enforce the measure to the hilt. The new battles, he would quickly learn, would be the most rugged he had ever fought.