Part IV: Regulating Cosmetics, Devices, and Veterinary Medicine After 1938

Quack products were the subject of most of FDA's device regulatory actions until the 1960s. Pictured here are assorted versions of orgone accumulators, developed by psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich to collect what he believed was an ethereal substance in the atmosphere vital to health and longevity.

Cosmetics and medical devices, which the Post Office Department and the Federal Trade Commission had overseen to a limited extent prior to 1938, came under FDA authority as well after 1938. While pre-market approval did not apply to devices, in every other sense the new law equated them to drugs for regulatory purposes. As the FDA had to deal with both increasing medical device quackery and a proliferation of medical technology in the post-World War II years, Congress considered a comparable device law when it passed the 1962 drug amendments. The legislation having failed to develop, the Secretary of HEW commissioned the Study Group on Medical Devices, which recommended in 1970 that medical devices be classified according to their comparative risk, and regulated accordingly. The 1976 Medical Device Amendments, coming on the heels of a therapeutic disaster in which thousands of women were injured by the Dalkon Shield intrauterine device, provided for three classes of medical devices, each requiring a different level of regulatory scrutiny--up to pre-market approval.

The 1938 act required colors to be certified as harmless and suitable by the FDA for their use in cosmetics. The 1960 color amendments strengthened the safety requirement for color additives, necessitating additional testing for many existing color additives to meet the new safety standard. The FDA attempted to interpret the new law as applying to every ingredient of color-imparting products, such as lipstick and rouge, but the courts rebuffed this proposal.

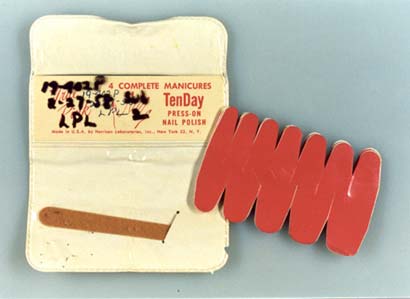

TenDay Press-On Nail Polish generated at least 700 consumer complaints in 1957, including several cases in which the nails broke off or split down to the quick. In February 1958, following an FDA press release warning against these synthetic nails, the manufacturer launched a nationwide recall of the goods.

Another agency responsibility, veterinary medicine, had been stipulated since the 1906 act; foods included animal feed, and drugs included veterinary pharmaceuticals. Likewise, animal drugs were included in the provisions for new drugs under the 1938 law and the 1962 drug amendments. However, the Food Additives Amendment of 1958 had an impact too, since drugs used in animal feed were also considered additives--and thus subject to the provisions of the food additive petition process. The Delaney Clause prohibiting carcinogenic food additives was modified by the DES proviso in 1962, named for diethylstilbestrol, a hormone used against miscarriages in humans and to promote growth in food-producing animals. The proviso permitted the use of possible carcinogens in such animals as long as residues of the product did not remain in edible tissues. The Animal Drug Amendments of 1968 combined veterinary drugs and additives into a unified approval process under the authority of the Bureau of Animal Drugs in the FDA.