How FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine Improved Human Healthcare During an Outbreak Linked to Puppies

QUICK SUMMARY

When an illness due to an outbreak of antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter didn't respond to first-line defense antibiotics, researchers in the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) designed a method to figure out what drug(s) could kill the bacteria. Their testing of different drugs against the antimicrobial resistant bacteria identified a drug which helped ill patients fight the infection. CVM’s testing also provided additional evidence for how the disease was spreading so it could be stopped at its source: pet store puppies. CVM’s efficient and effective actions seemed effortless but reflected years of experience working at the intersection of human and animal health. This compelling story underscores why public health can benefit from a One Health approach: an approach that recognizes the close connection between people, animals, and their shared environment and seeks the best health outcomes for all.

THE DETAILED STORY

Call to Action

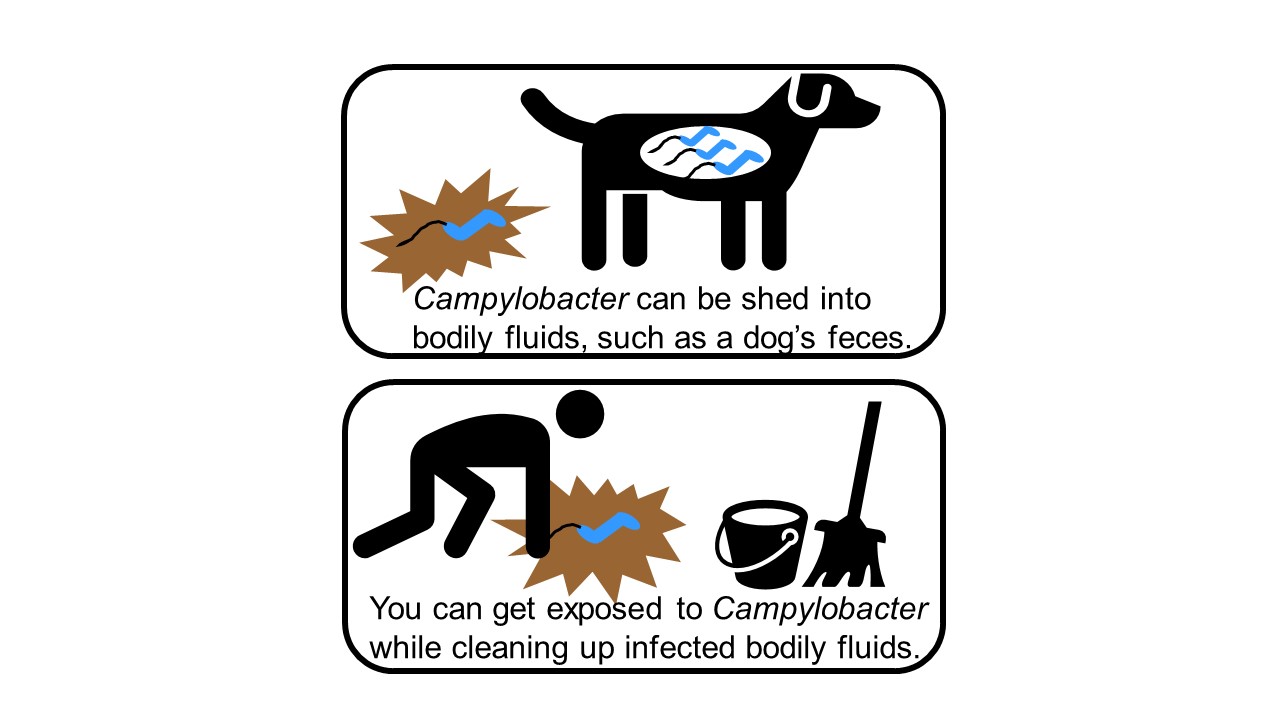

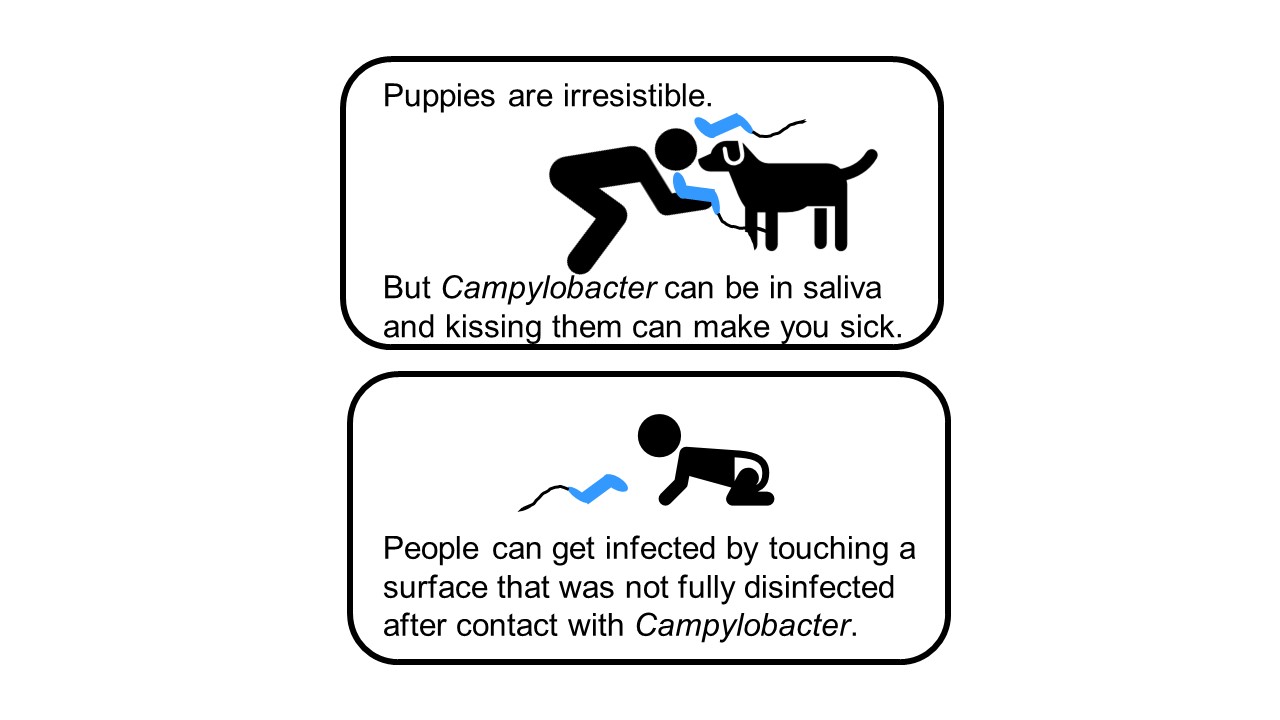

It started with a phone call. In October 2017, Dr. Patrick McDermott, then a Division Director in FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine's Office of Applied Science, received a call from a colleague at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) about a multistate outbreak of multidrug resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections. While most Campylobacter infections are related to food or farm animals, this one was linked to an unlikely and adorable source: pet store puppies. Folks of all ages are drawn to puppies, and the 113 people with reported infections ranged from 1 to 86 years old. People with Campylobacter infections normally need only supportive care and usually don’t need antibiotics to recover, but this infection was different. Testing on bacterial samples isolated from patients (“isolates”) showed that the infection was resistant to all first-line defense antibiotics. CDC asked if the FDA team could do additional laboratory testing to identify an effective antibiotic to treat people sickened by this strain of Campylobacter.

Assessing the Threat

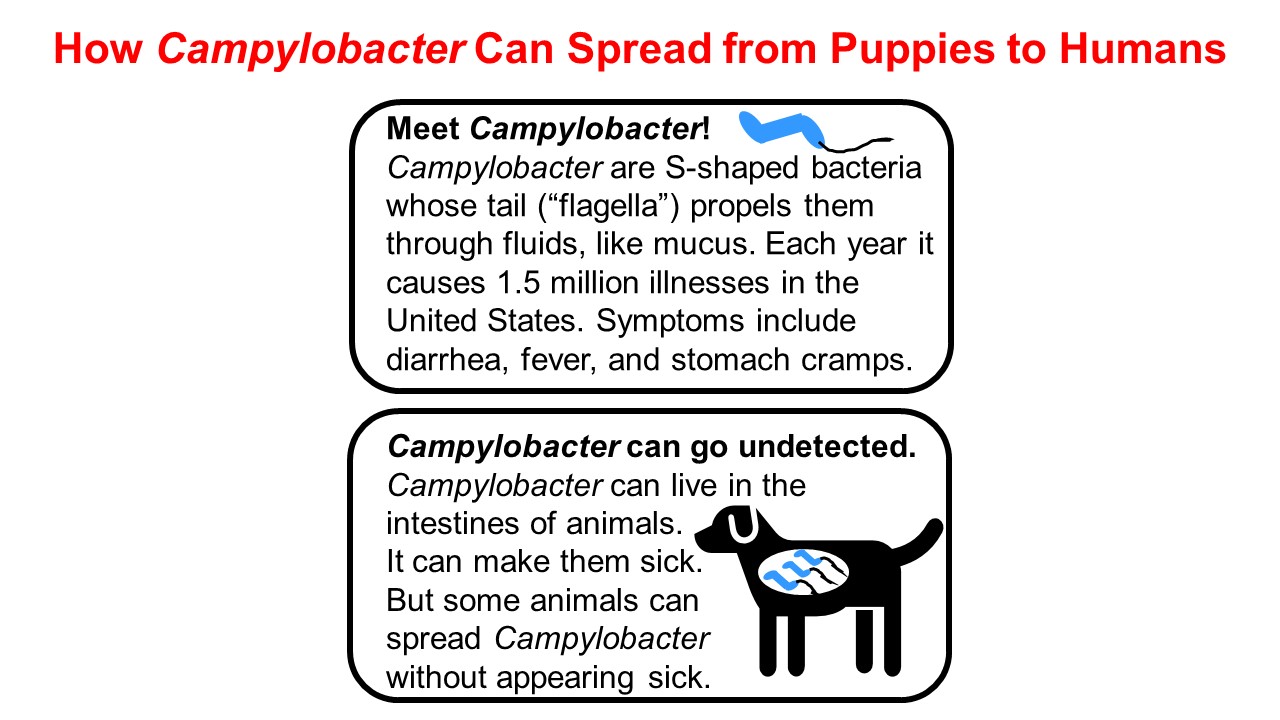

Campylobacter is one of the most common bacterial causes of diarrheal illness in the United States. Although most of the 1.5 million U.S. residents infected with Campylobacter each year recover on their own, some people – particularly those who are immunocompromised – develop serious and even life-threatening infections. An effective treatment for the extensively drug-resistant strain was needed to treat some patients.

How CVM Fits In

As a partner in the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS), an interagency partnership among the FDA, CDC, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CVM regularly tests retail meat across the United States for bacteria and monitors for the development of antimicrobial resistance. The CDC called the FDA for help identifying additional antibiotics that might work against the extensively drug resistant strain of Campylobacter.

Dr. McDermott’s team designed the testing approach that's routinely used to measure how well antibiotics work against Campylobacter. That routine testing approach, called broth microdilution, involves mixing nine antibiotics at different concentrations with bacteria and observing what stops their growth. However, the Campylobacter strain causing patients to get sick during the outbreak wasn’t responding to any of the nine antibiotics in the testing panel, so the FDA team set out to design a new approach to testing additional antibiotics against Campylobacter.

Getting to Work

CDC sent bacterial isolates to FDA collected from four ill people and eight puppies. During the outbreak investigation, patient interviews indicated that 99% had contact with a puppy in the week before getting ill, so it was important to find out if the bacteria in humans and puppies responded to antibiotics in the same way. The FDA team used its understanding of existing antimicrobial testing methods to quickly design and validate an expanded testing approach for more than 30 antibiotics. After many late nights with numerous scientists helping in the lab, the FDA team identified three antibiotics that were able to stop the extensively drug-resistant strain of Campylobacter from growing. The FDA team shared this information with CDC staff, who considered those options and decided that the drug with the highest chance of success in human patients was imipenem – a medicine that would not otherwise have been selected for the treatment of a Campylobacter infection.

Seeing the Impact

The FDA team felt a tremendous sense of reward knowing that their hard work identified an antibiotic to recommend for treating patients with multidrug resistant Campylobacter infections. Working in a research lab, however, they did not expect to see the direct impact of their work. But several months later, they received a second call which provided that perspective. Two patients had been hospitalized with serious, multidrug drug resistant Campylobacter infections. One after another, antibiotics that were expected to fight Campylobacter, including ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and azithromycin, failed to clear the infection in the patients. With time running out, their doctor sought another option. An alert from the CDC about the ongoing Campylobacter outbreak in puppies pointed to a promising treatment. It was the drug identified by the FDA’s research. After weeks of debilitating illness, both patients were treated with imipenem, as customarily dosed in combination with a drug called cilastatin. Both recovered soon after receiving the treatment and were able to go home from the hospital.

To check whether the patients had the same strain of Campylobacter that was spreading during the outbreak, the FDA team tested bacterial isolates from the patients. The team used its method of testing more than 30 antibiotics to find out what drug the patients' multidrug resistant Campylobacter infections responded to in the laboratory. As with isolates of the outbreak strain tested months earlier, isolates from these two patients responded to imipenem. This laboratory result provided additional evidence that they recovered from the infection due to their treatment with imipenem with cilastatin.

Providing Important Links

In addition to testing Campylobacter isolates from the two patients, the FDA team tested Campylobacter isolates from a puppy belonging to one of the patients. Bacteria collected from the puppy responded to antimicrobial drugs in a similar way as the Campylobacter sampled from its owner. This provided evidence of a link between the bacteria making people and puppies sick.

This research was recently described in a publication titled, “Antibiotic susceptibility testing and successful treatment of hospitalised patients with extensively drug-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections linked to a pet store puppy outbreak” in the Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. In addition, this work was recently presented via a poster during the 2021 FDA Science Forum.

Vet-LIRN’s Contribution to the Outbreak Response

The FDA’s Veterinary Laboratory Investigation and Response Network (Vet-LIRN), a CVM-funded partnership among 46 veterinary diagnostic laboratories, played an important role in the Campylobacter outbreak investigation, as well. Vet-LIRN coordinated the collection of bacterial isolates from dogs in the homes of ill people for testing by network laboratories. Vet-LIRN also funded the development of a simple and safe method to obtain DNA samples from the Campylobacter infecting puppies to test for a genetic link between the Campylobacter strains making humans and puppies sick. Whole genome sequencing of Campylobacter isolates by the FDA, CDC, and state laboratories showed that DNA in bacteria collected from ill humans was similar to DNA in bacteria collected from puppies. Patient interviews and whole genome sequencing data corroborated each other and this evidence of a link between human and puppy infections helped investigators track down the source of the outbreak. In addition, Vet-LIRN coordinated antimicrobial susceptibility testing on isolates collected by the Ohio Department of Agriculture’s Animal Disease and Diagnostic Laboratory. Note that the FDA team that designed the expanded broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility approach for testing more than 30 antibiotics against Campylobacter performed the antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the Ohio samples, highlighting how well these different teams in the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine worked together to respond to the outbreak. You can learn more about Vet-LIRN’s role in the investigation in this article.

One Health in Action

Are you surprised to hear that the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine worked to find an antibiotic that could treat human patients? It makes sense when you consider that CVM’s mission is to protect human and animal health. Every day, CVM conducts research to assure the safety of the food that we get from animals and the safety and efficacy of medical products we administer to animals. Seeking optimal health outcomes for humans and animals in their shared environment is known as the One Health approach, and CVM staff apply One Health thinking in everything they do. Want to learn more? You can read more about the range of FDA’s One Health activities here.

Putting it all in Perspective

Most of the time, the connection between human and animal health is mutually beneficial. Less than 15% of Campylobacter illnesses in the U.S. each year are associated with animal contact, and human illness due to contact with domestic puppies is linked to less than 5% of Campylobacter infections. Although many patients were hospitalized with serious Campylobacter infections during the outbreak, all survived. The FDA’s work to identify an effective antibiotic and CDC's issue of an alert to physicians likely contributed to this successful clinical outcome.

It is important to note that the efficient and effective response to this outbreak by FDA CVM, CDC, and state and local agencies did not come together overnight in response to an emergency. It was the result of expertise at the intersection of human and animal health that developed over many years. That expertise has been gained through research the FDA’s CVM performs in collaboration with partners across the federal government through NARMS and with laboratories across the U.S. through Vet-LIRN.

At the core of these programs are dedicated staff in the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine that work hard to assure that all the adorable pets and animals in our lives have safe and effective medicines and safe food. They, too, have pets and other animals in their families and appreciate how vital animal health is to our health and to the health of the planet. Responsible use of antibiotics in humans and animals, known as antimicrobial stewardship, is an important step in preserving antibiotics for our future use.