Three-Dimensional (3D) Cell Culture (Microphysiological) Platforms as Drug Development Tools

CDER researchers are investigating cell culture platforms that can supplant the need for animal testing or clinical trials in specific regulatory contexts. These platforms recreate three-dimensional (3D) physiological settings in vitro that enhance the clinical relevance of cultured organ-specific cell functionality. CDER scientists are researching the capacity of these platforms, given their demonstrated potential to replicate human physiology, to yield reproducible results following quality control criteria and functional performance standards. These criteria and standards will be essential to the requisite validation of such platforms for specific contexts of use.

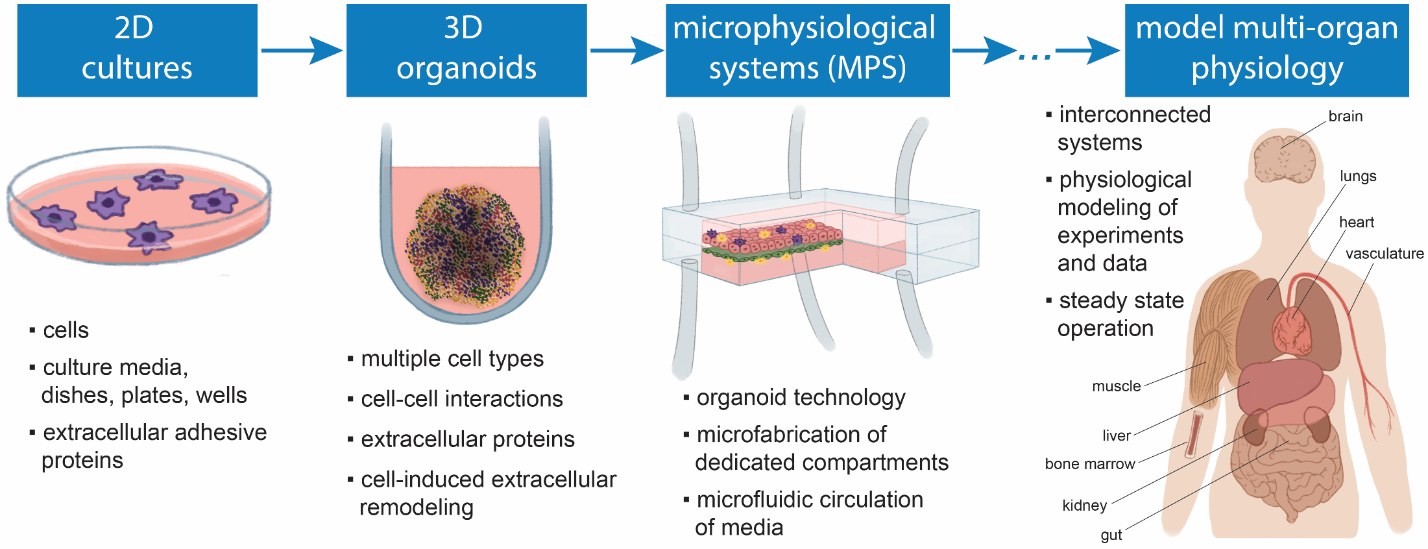

Our ability to investigate drugs with respect to their pharmacology, efficacy, and toxic side effects on specific organs is crucial the development of new therapeutic products. This ability, however, is often limited by the availability of model systems (e.g., animal models or cell cultures) that can properly recapitulate the physiological dynamics of human tissues in vivo, particularly when the mechanistic bases of unexpected clinical results must be further investigated. These challenges can lead to drug attrition in the late stages of a costly drug development process. Novel platforms, in which human tissue-specific cells are cultured and physiologically enhanced in 3D, have the potential to address these challenges and improve the efficiency of drug development (Figure 1). 1 To further its mission to translate new science into the drug development process, the Division of Applied Regulatory Science (DARS) 2 in CDER is characterizing these innovative platforms as potential drug development tools.

Figure 1. Culturing cells in 3D as advanced platforms to model physiological properties in vitro. Petri dishes and similar two-dimensional (2D) cell culture platforms have been used for almost a century for attempting to predict clinical drug effects. More recently, 3D platforms have made it possible to simultaneously co-culture different cell types that represent tissue-specific cellular varieties in a 3D configuration to recreate more physiologically relevant settings in vitro. Learn more.

A Focus on Liver and Cardiac Platforms

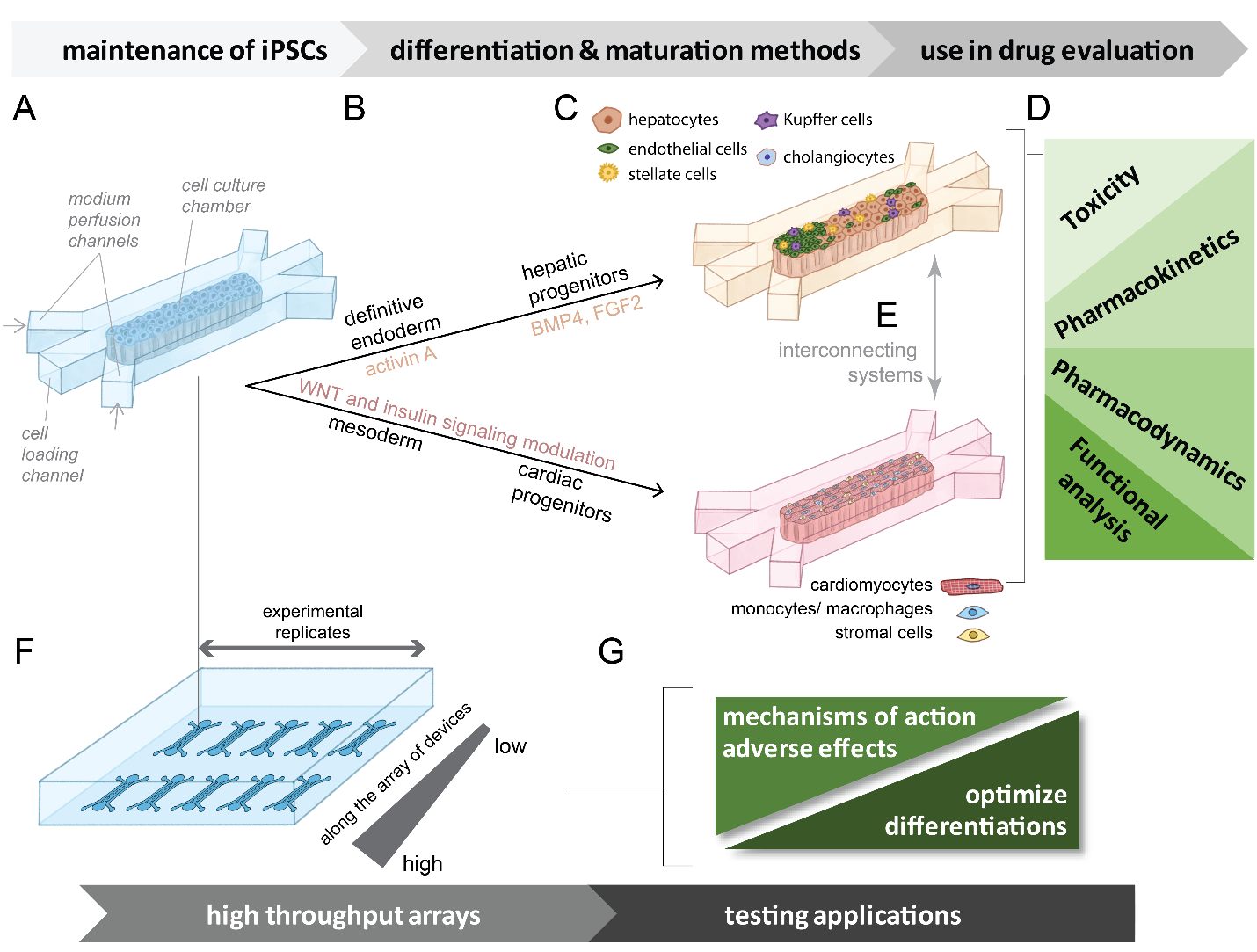

Because cardiotoxicity and hepatotoxicity are the main causes of drug attrition, liver- and heart-specific 3D cell culture platforms have been an important focus of DARS investigators. The role of the liver in drug clearance and metabolism, moreover, is central in pharmacology. 3 In addition to using cells isolated from humans, 4 ,5 CDER researchers have been investigating the possibility of using cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Figure 2), which have the potential to be a renewable source of cells with specifically tailored genetic backgrounds. 6 ,7 By exposing perfused stem cells to different levels of stimuli (e.g., growth factors, small molecules, media supplements), functionally mature cardiac and hepatic cells can be created and combined into well-defined heterogenous co-cultures for high throughput assays. Because cardiotoxicity can also result from the metabolism of prodrugs in the liver, CDER researchers are also investigating the applications of an interconnected liver-heart microplatform, 8 and there are plans to investigate gut-liver interconnected systems and lung and kidney platforms as well.

Figure 2. Possible device array systems for the differentiation of iPSCs to hepatic or cardiac lineages that can be interconnected and used to analyze effects. (a) General schematic of a single device unit containing a chamber for initial iPSC culture. Cells can be loaded through an engineered inlet and the culture can be maintained by media perfused through parallel channels. (b) Directed differentiation from iPSCs to specified lineages (hepatic or cardiac) can be performed at scale within the chambers. Media containing differentiation signals (growth factors, small molecules, media supplements) is perfused through the channels based on established differentiation methods are indicated for cardiac and hepatic stem cells. (c) Co-cultures that support both cardiac and hepatic functional maturation can be created by loading mixtures of cell types into the chambers. (d) Examples of functional endpoints that can be evaluated using these types of developed systems. (e) Multi-organ systems can be simulated through connecting systems loaded with different cell types. (f) Graphical representation of a device array designed for miniaturized higher throughput experimental capacity. Gradients of variable conditions can be established through microfluidic controls. (g) Examples of screening applications that can be performed on miniaturized higher throughput arrays of devices. These systems may offer a platform for the screening evaluation of drugs affecting cell function. Learn more.

Quality Control Criteria to Ensure the Reproducibility of Liver Microphysiological Systems and Engineered Heart Tissues

The reproducibility of microengineered 3D platforms is central to their translation to drug development and regulatory applications. The reproducibility of a liver 3D microphysiological system was characterized in CDER laboratories with the intent of investigating potential performance standards.4 This characterization aimed to address the suitability of such a system to applications in drug safety risk assessment 9 and pharmacology.10 Study outcomes showed that system functional robustness could be achieved when following quality control criteria that are based on non-destructive and minimally invasive assays related to cell viability and metabolism.4 Using trovafloxacin as a hepatotoxic drug and levofloxacin as a non-hepatotoxic drug, and following quality control criteria, reproducibility was achieved between different experimental sites and when using different qualified batches of liver cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of results with trovafloxacin and levofloxacin added to a liver 3d microphysiological system, where reproducibility of effects was observed across experimental sites, using distinct batches of Kupffer cells, while following quality control criteria for these cells.

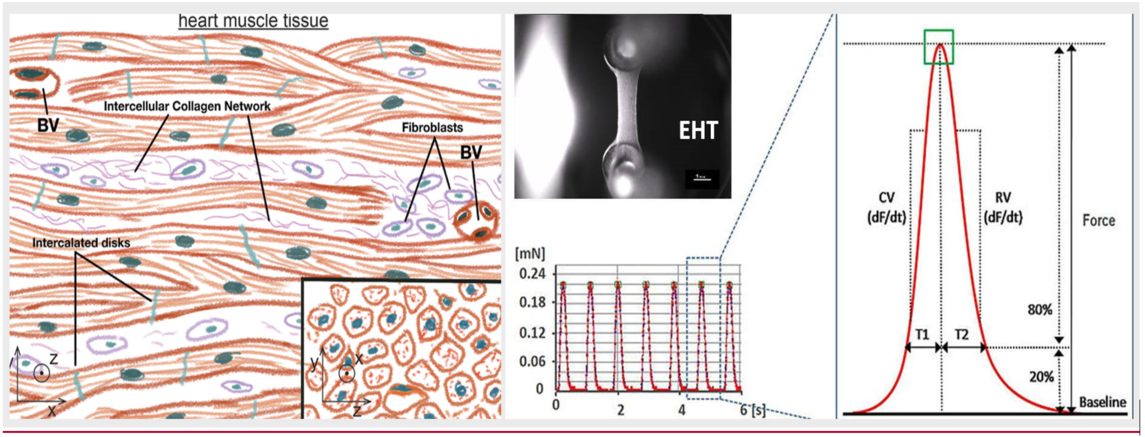

This effort also resulted in a list of general recommendations for qualifying liver systems that complement what was already published, 9 ,10 which are key for developing in vitro liver platforms. CDER researchers have also been assessing the reproducibility of drug-induced variations in the contractility of 3D engineered heart tissues (EHTs; Figure 4). 11 These platforms have the advantage of lasting over a month in culture and therefore have the potential to be used in the evaluation of cardiotoxicity resulting from long-term exposure to a drug. To ensure the reproducibility of these systems, their assembly properties and how they remodel themselves over time are being characterized. Since focus is being given to contractility as a functional endpoint (Figure 4), the researchers also made sure to characterize the maturity of the EHT contractile function.

Figure 4. Engineered heart tissues (EHTs) recapitulate the 3D nature of heart muscle tissue (e.g., contractile alignment), as shown on the left [blood vessels, (BVs)]. By immobilizing these tissues between force sensors as shown on the right, CDER researchers analyzed drug-induced variations in the contractility of these platforms and derived functional parameters.

Future Work, Contexts of Use, and Additional Systems under Investigation

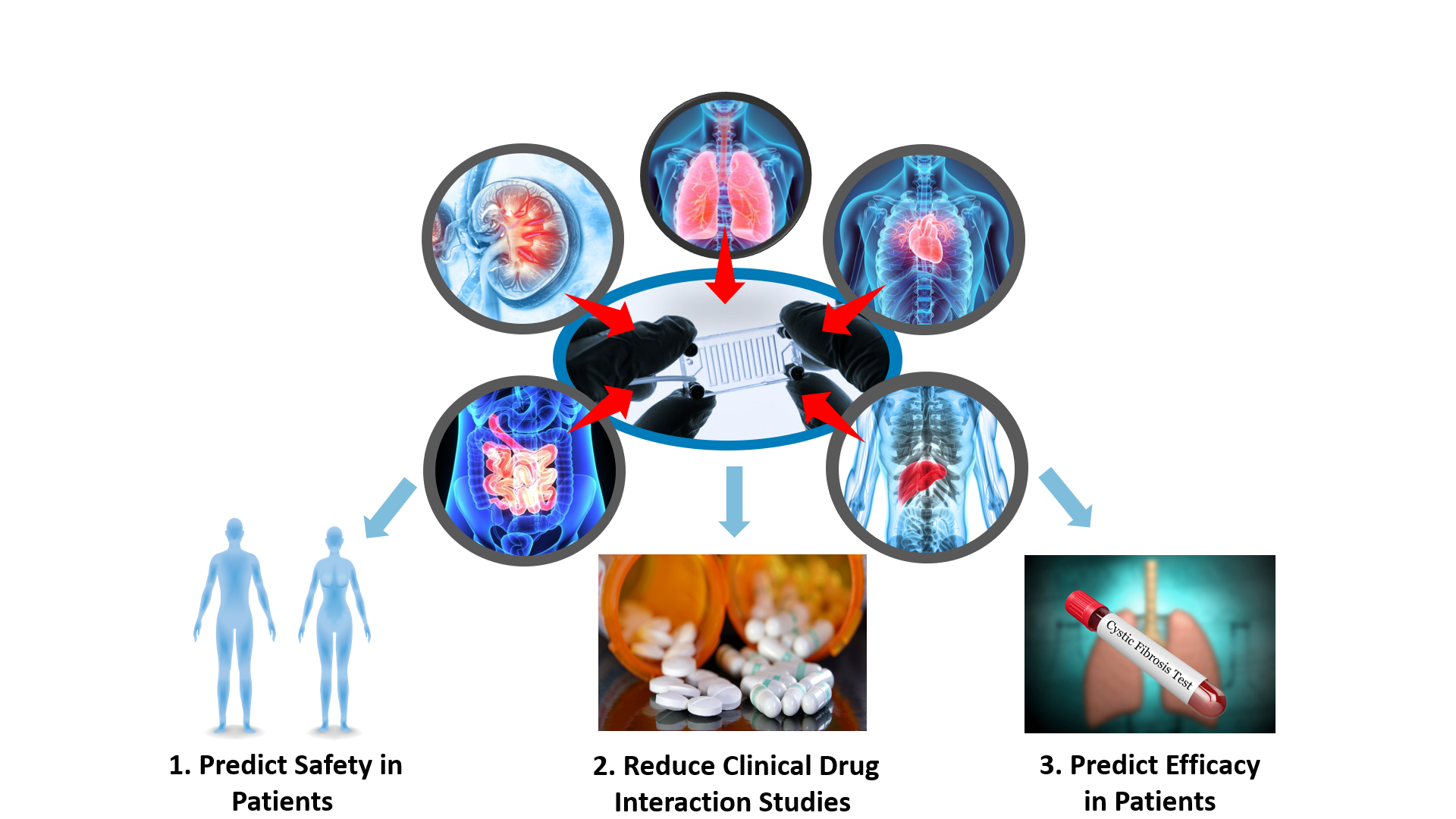

3D cellular microplatforms with enhanced physiological settings have also been developed to model properties of other organs with relevance to drug development, such as gastrointestinal tissues, kidney, and lung. In the coming years, DARS plans to expand research efforts to platforms modeling other organs (e.g., kidney, lung, gut-liver interconnected systems) to establish quality control criteria and general performance standards. In parallel, CDER researchers are exploring the application of 3D cellular microplatforms to drug-drug interactions, derisking drug safety signals, generic drug development, and rare diseases modeling (Figure 5). Organ-specific microplatforms also have the potential to facilitate many regulatory tasks related to FDA-regulated products, and CDER will work collaboratively with stakeholders to standardize the reproducible and robust regulatory use of this technology.

Figure 5. CDER researchers are expanding the scope of their efforts in the field of 3D cellular microsystems to other organ types (kidney, lung and gastrointestinal) and starting to focus on critical questions in contexts of use related to derisking drug safety signals (1), predicting clinical drug-drug interactions (2) and the efficacy of generic drugs and new drugs to reduce or replace the need of clinical trials.

How does this research improve the drug development process?

CDER researchers are characterizing the reproducibility of 3D cell culture microplatforms with enhanced physiology to produce data that will support the development of guidance for industry on quality control and performance standards for using this technology in drug development. Initial work focused on liver and cardiac organ microsystems and is now evolving to other organ models to focus on critical contexts of use in the areas of derisking drug safety signals, drug-drug interactions and drug efficacy. This research has the potential to streamline drug development by reducing or replacing animal studies and/or clinical trials in contexts of use related to the micromodels being studied.

- 1Wang H, Brown PC, Chow ECY, Ewart L, Ferguson SS, Fitzpatrick S, Freedman BS, Guo GL, Hedrich W, Heyward S, Hickman J, Isoherranen N, Li AP, Liu Q, Mumenthaler SM, Polli J, Proctor WR, Ribeiro A, Wang JY, Wange RL and Huang SM. 3D cell culture models: Drug pharmacokinetics, safety assessment, and regulatory consideration. Clin Transl Sci. 2021.

- 2Rouse R, Kruhlak N, Weaver J, Burkhart K, Patel V and Strauss DG. Translating New Science Into the Drug Review Process: The US FDA's Division of Applied Regulatory Science. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52:244-255.

- 3Dame K and Ribeiro AJ. Microengineered systems with iPSC-derived cardiac and hepatic cells to evaluate drug adverse effects. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2021;246:317-331.

- 4 a b c Rubiano A, Indapurkar A, Yokosawa R, Miedzik A, Rosenzweig B, Arefin A, Moulin CM, Dame K, Hartman N, Volpe DA, Matta MK, Hughes DJ, Strauss DG, Kostrzewski T and Ribeiro AJS. Characterizing the reproducibility in using a liver microphysiological system for assaying drug toxicity, metabolism, and accumulation. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14:1049-1061.

- 5Miller JM, Meki MH, Ou Q, George SA, Gams A, Abouleisa RRE, Tang XL, Ahern BM, Giridharan GA, El-Baz A, Hill BG, Satin J, Conklin DJ, Moslehi J, Bolli R, Ribeiro AJS, Efimov IR and Mohamed TMA. Heart slice culture system reliably demonstrates clinical drug-related cardiotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020;406:115213.

- 6Maddah M, Mandegar MA, Dame K, Grafton F, Loewke K and Ribeiro AJS. Quantifying drug-induced structural toxicity in hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes derived from hiPSCs using a deep learning method. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2020;105:106895.

- 7Qosa H, Ribeiro AJS, Hartman NR and Volpe DA. Characterization of a commercially available line of iPSC hepatocytes as models of hepatocyte function and toxicity for regulatory purposes. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2021;110:107083.

- 8Lee-Montiel FT, Laemmle A, Charwat V, Dumont L, Lee CS, Huebsch N, Okochi H, Hancock MJ, Siemons B, Boggess SC, Goswami I, Miller EW, Willenbring H and Healy KE. Integrated Isogenic Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Liver and Heart Microphysiological Systems Predict Unsafe Drug-Drug Interaction. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:667010.

- 9 a b Baudy AR, Otieno MA, Hewitt P, Gan J, Roth A, Keller D, Sura R, Van Vleet TR and Proctor WR. Liver microphysiological systems development guidelines for safety risk assessment in the pharmaceutical industry. Lab Chip. 2020;20:215-225.

- 10 a b Fowler S, Chen WLK, Duignan DB, Gupta A, Hariparsad N, Kenny JR, Lai WG, Liras J, Phillips JA and Gan J. Microphysiological systems for ADME-related applications: current status and recommendations for system development and characterization. Lab Chip. 2020;20:446-467.

- 11Mannhardt I, Breckwoldt K, Letuffe-Brenière D, Schaaf S, Schulz H, Neuber C, Benzin A, Werner T, Eder A, Schulze T, Klampe B, Christ T, Hirt MN, Huebner N, Moretti A, Eschenhagen T and Hansen A. Human Engineered Heart Tissue: Analysis of Contractile Force. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;7:29-42.